About this doc

There is a glossary at the bottom. It’s my distillation of a few days of FX market research; please reach out if anything is confusing.

FX Spot Markets

Spot FX as a whole is decentralized; there is no universally agreed upon clearing house.

Most spot FX is T+2; except USD/CAD and a few others which are T+1. The FX market operates 24/5 across various electronic platforms and dealer networks. Trades can be executed via interdealer brokers (e.g. EBS, Refinitiv Matching), multi-bank trading platforms (e.g. FXall, 360T, Bloomberg FXGO), single-dealer platforms, or voice/chat channels for less liquid trades. The rise of electronic communication networks (ECNs) and request-for-quote (RFQ) platforms has driven high efficiency: in major currency pairs, most pricing is electronic and often automated via algorithms. Global banks (e.g. JPMorgan, Citi, UBS, Deutsche Bank) remain key market-makers, collectively providing much of the liquidity and credit that underpins FX trading. However, non-bank liquidity providers (proprietary trading firms like XTX Markets, Citadel Securities, etc.) have grown in influence, streaming competitive prices on electronic venues. These players benefit from prime brokerage arrangements that grant them access to the same anonymous trading venues as banks. Prime brokers (often large banks) act as intermediaries that allow clients (funds, retail brokers, fintechs) to trade with numerous counterparties under a single credit line. This structure has enabled broad market access but concentrates credit risk in prime banks.

What venues exist for FX?

- Refinitiv (LSEG) FX platforms: ~$100 billion/day in spot across Matching and FXall combined (peaking at $109B in Sep 2024), and about $378B/day in forwards/ swaps. FXall is the leading multi-dealer platform for corporate/investor flow.

- CME EBS: Roughly $60 billion/day average spot in 2024 (with highs above $70B), after a dip in 2023. CME is launching “FX Spot+” to integrate EBS more with its futures, indicating strategic importance.

- Cboe FX (Hotspot): In the $40–50B/day range in spot. Notably strong in certain pairs and during US hours. Hit record volumes in April 2024 amid yen volatility.

- FXSpotStream: ~$50B/day in 2024 (spot). It’s a unique aggregated streaming RFQ service (a bank consortium that provides a single API for clients to get quotes from all 15+ member banks). It had a surge in Q4 2024 volumes (+25% from Q1), showing regained growth.

- 360T: ~$168B/day total in 2024 across products (spot + swaps). It had record non-spot (forward, swap) volumes – e.g. NDF volumes rose to $1.74B/day. 360T’s spot component is smaller than its swaps but still significant (~$20–30B).

- Euronext FX (ex-FastMatch): On the order of ~$20B/day spot in 2024, after some growth. It had peaks in late 2024 with US election-related trading.

- LMAX Exchange: A London-based FX ECN focused on funds/prop traders, known for cryptocurrency as well. FX ADV possibly in tens of billions (LMAX doesn’t publicly report, but it’s recognized as a top FX venue).

- Regional/local venues: e.g. FXMarkets TX (Singapore), Currenex (now part of State Street), and Integral each may handle single-digit billions daily. Bloomberg FXGO handles very large ticket notional (especially for corporate and central bank trades) but as an RFQ hub with no centralized tape, volumes aren’t disclosed.

Importantly, a chunk of FX trading still happens via voice brokers and direct bilateral trades, especially for less liquid currencies or large hedge funds dealing directly with bank desks. Interdealer brokers like TP ICAP and BGC facilitate voice matching for pairs like USD/TRY, USD/KRW, or when big flows need discretion. The BIS 2022 survey indicated about 15% of FX turnover might still be via phone or unstructured methods, but this share is declining as e-trading reaches into those areas too.

Risk types

TLDR:

- For dealers: A bank’s FX trading desk measures market risk using metrics like Value-at-Risk (VaR) – e.g. a daily 99% VaR of $5 million means there’s a 1% chance the desk loses more than $5m in a day based on historical volatility. Banks set position limits (e.g. cannot be more than $X net long in any currency) and stop-loss limits to control traders. They also perform stress tests simulating extreme moves (like a 10% overnight devaluation) to see potential losses and ensure they’re within tolerances or covered by capital. Traders use tools like stop-loss orders to cut positions if the market goes against them beyond a point. Some firms also hedge dynamically – for instance, an importer with a large USD payable might buy a forward, removing its FX market risk and converting it to a known cost.

- For investors: A global fund will measure FX exposure on its portfolio and may use FX VaR or scenario analysis (e.g. if USD drops 5%, portfolio value changes by Y). They may hedge part of their exposure to reduce this risk.

- For corporates: The risk is that currency moves could reduce their local currency revenues or increase costs. They manage it by hedging as discussed – converting an uncertain future rate to a fixed rate via forwards/options, thus trading market risk for known cost (and possibly some premium cost).

- Market risk can also come from volatility: e.g. an options writer is at risk if volatility spikes (option values rise). They manage it by delta hedging (adjusting underlying positions as market moves) and using risk limits on “greeks” like vega (sensitivity to vol) and gamma (sensitivity of delta to spot changes).

In more detail below.

Credit risk (counterparty risk)

In FX, this arises primarily in forward or swap contracts (where there’s a period between trade and settlement) and when settling trades (one party could deliver funds and the other fails).

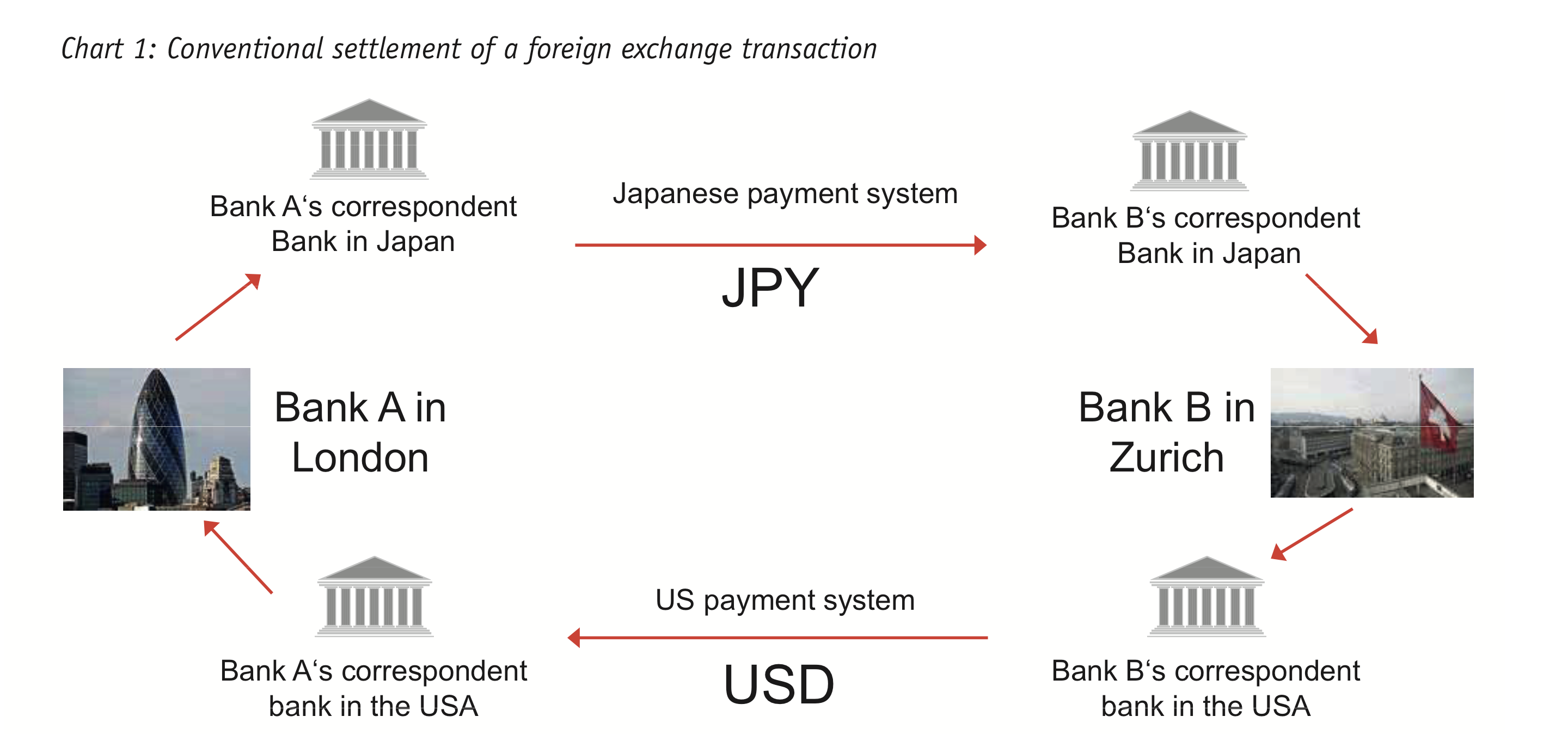

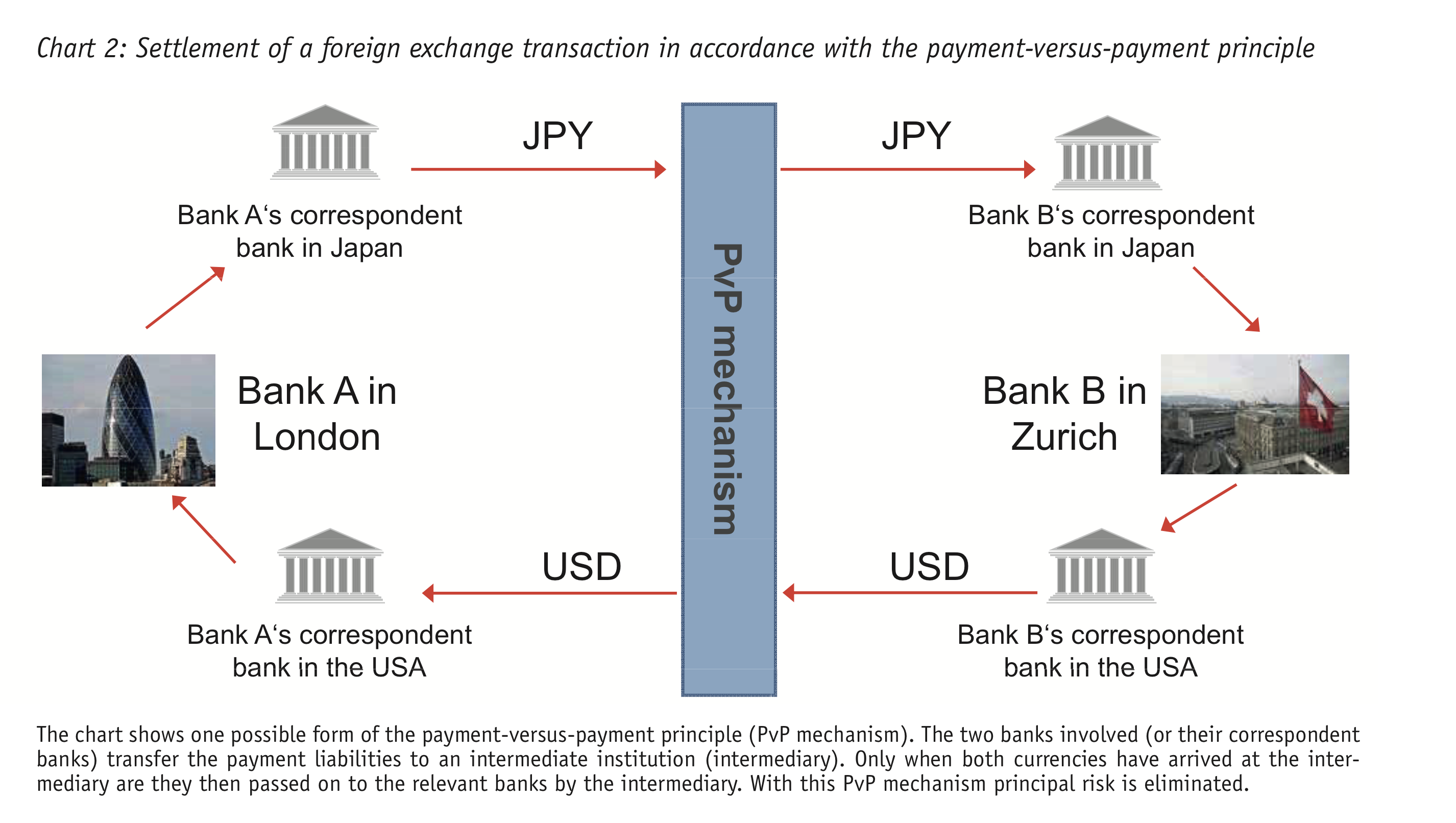

- The worst historical example was Herstatt Bank in 1974: it received Deutschmarks in Frankfurt but failed before delivering dollars in New York (thus “Herstatt risk”). Settlement risk is largely addressed by CLS Bank’s PvP mechanism, which now covers the bulk of major currency trades. For trades outside CLS, parties often limit exposure via bilateral payment netting and using correspondent banking arrangements that allow cancellation if the other fails to pay. See CLS section.

- For forwards/derivatives, counterparty credit risk is mitigated by netting agreements (ISDA) and margin (collateral). The majority of interdealer FX forward and swap exposure is covered by daily variation margin under CSAs. If one party defaults, the other can close-out the net position and use collateral to cover losses.

- Prime brokerage setups concentrate counterparty risk on the PB (the client trades with many parties but the PB is the legal counterparty to all those trades). The PB manages this by requiring initial margin and default fund contributions. E.g. a prime broker will stop a client from trading or liquidate positions if their margin falls too low, thus preventing a scenario where the client can’t pay the counterparties.

- Non-bank participants: Corporates usually have credit lines with banks for forwards. If a corporate approaches its credit limit (mark-to-market losses on forwards), the bank may ask for early settlement or margin. Some corporates preemptively post collateral for large long-dated hedges to reduce bank credit charges.

- A metric regulators watch is CVA (Credit Valuation Adjustment) – essentially the market value of counterparty credit risk. Banks must hold capital for potential CVA losses (the risk that a counterparty’s credit worsens and the derivative MTM would have to be adjusted). This has incentivized more clearing of FX derivatives to remove bilateral CVA risk.

Liquidity risk

The risk that one cannot transact or liquidate positions without significant cost.

- Market Liquidity Risk: In major FX pairs, liquidity is usually ample, but it can evaporate in crises or off-hours. Participants manage this by maintaining appropriate position sizes relative to market depth. E.g. a hedge fund won’t build a huge position in an emerging currency where the market is thin without expecting difficulty exiting. Traders set position limits that consider liquidity (tight limits for exotic currencies). Stop-loss orders and options can provide some protection if market gaps (though stops might get filled at worse levels in a gapping market).

- Central banks sometimes provide liquidity indirectly by stepping in during dysfunction (e.g. Fed swap lines ensure USD liquidity globally, reducing panic demand). For individual firms, having access to multiple execution venues and counterparties mitigates liquidity risk – if one LP withdraws quotes, they can still trade with others.

- Funding Liquidity Risk: Ensuring the ability to meet cash obligations, such as margin calls or settlement payments. E.g. in a volatile FX move, a hedge fund might get a margin call from its PB – it needs readily available cash or lines of credit to meet it, or else positions will be cut at a possibly inopportune time. Firms manage this by keeping buffer cash or credit lines. Corporates ensure they have cash in the right currency accounts by settlement day (often facilitated by doing FX swaps to bridge timing gaps).

- Banks manage intra-day liquidity for settlements – e.g. ensuring they have enough of each currency in CLS by funding deadlines. If a currency is scarce, they might borrow from another bank or central bank for a day. The Basel III LCR (Liquidity Coverage Ratio) forces banks to hold high-quality liquid assets enough to cover 30-day outflows, which includes FX swap payables, etc., thus formalizing liquidity risk management.

Operational risk

The risk of loss due to failed processes, human error, system failure, or fraud. These are pretty obvious; fat finger, rogue employee, etc.

Compliance Risk

- Fixing manipulation: Banks have compliance processes to handle fixes now. They no longer allow sharing of fix order info among dealers at different banks (Global Code strongly forbids this information sharing beyond what’s necessary).

- Last Look abuse: Compliance monitors reject ratios and hold times. The Code says last look should be “transparent and fair”. If a bank systematically only rejects when trade would be bad for them but fills when it’s good (asymmetric last look), that’s considered misconduct. Many liquidity providers publish their fill ratios.

- AML/Sanctions: In cross-border payments, ensuring currencies aren’t being used for laundering is big. Banks use sanctions screening on payment messages (e.g. halt any payments involving sanctioned entities). FinCEN, OFAC, etc., enforce heavy fines if banks facilitate forbidden flows. E.g. banks had to ensure after Russia sanctions in 2022 that they don’t trade with designated Russian banks or help clients circumvent ruble restrictions.

Post-2008 reforms:

- Basel III’s Leverage Ratio makes sure even off-balance sheet FX exposures count in leverage calculations (through add-ons). Initially, it was harsh (counted full notional of derivatives), but now uses standardized exposure method (less punitive for short-dated FX).

- Capital Buffers: Banks hold capital for market risk (VaR or stressed VaR), for credit risk (counterparty risk on derivatives), and for operational risk (basel op risk charge).

- The BIS monitors banks’ FX settlement exposures via periodic surveys and has pushed banks to improve PvP adoption. Supervisors may require banks that still settle a lot outside CLS to hold more capital or liquidity against that settlement exposure.

Settlement infrastructure

CLS

TLDR; CLS is an atomic settlement method for payments. It nets out trades letting ~60-70 banks settle <2% of their gross trades.

If there is no direct account relationship between two operators on the foreign exchange market, foreign exchange transactions are traditionally settled via correspondent banks. In this case, when one party meets its obligation irrevocably, it does so without knowing whether its counterparty will settle its liability. This means that there is a risk of the counterparty delivering late (liquidity risk) or, in the worst case, not at all (credit risk). These risks are compounded if the foreign exchange market participants are in different time zones.

The famous case of this was Herstatt bank; tldr, in 1974, a German bank FTD’d 2b German Marks, and due to timezone differences (USD sent in exchange for Marks settled before the Marks were to be sent the following day), their counterparty failed to receive their USD payments. This led to a slow system for ~20yrs where there there was a third party escrow system, eliminating principal risk.

Participation in CLS can be either direct (settlement member) or indirect (third party). There are ~60 settlement member banks. All must have an equity stake in CLS. The important features for these banks is as follows:

- Account with CLS

- 18 currency-specific subaccounts

- self-collatrealizing transactions; ie, a liability in one currency is always covered by a claim in another currency

In theory, this is pretty easy; every party sends the currency they sell into CLS, and it settles both sides. But t+2 is liquidity inefficient. To solve this, settlement is separated from payment flows; meaning that they are settled on a gross basis, but then payment is netted. Meaning that only the net positions of a settlement member is transferred. CLS claims that ~2% of gross amounts are ever actually settled in cash.

In practical terms, for each FX trade, the operational flow is:

- Trade Confirmation: Right after execution, counterparties (or their prime brokers) confirm the trade details, often through electronic messaging (SWIFT MT300 or protocols like FIX). Many use services like MarkitSERV or GTX Post-Trade to match details. Misconfirmation is an operational risk, though nowadays STP means trade tickets go straight from platform to back-office systems.

- Netting: If a bank has 100 trades today with another bank, they will net all the USD pays and receives into one net USD amount, same for EUR, etc., typically by value date.

- Settlement Instruction: If using CLS, both submit the instructions to CLS (or via a third-party member). If not, they send SWIFT MT202 payment orders through correspondent banks. SWIFT gpi gives a UETR (unique end-to-end ID) to track.

- Funding: On settlement date, CLS will require each member to pay in the currency they owe by a certain cutoff (during a window around 6–9am London depending on currency). For non-CLS, parties must ensure they have funds in their correspondent account. Some markets require prefunding for NDFs (e.g. in certain clearinghouses).

- PvP/Finality: In CLS, once all pay-ins received, it simultaneously pays out the currencies to the respective receivers – completing the chain. Outside CLS, each payment is final when settled in that currency’s RTGS (Fedwire, etc.), but without PvP the two legs are not linked.

As such CLS:

- Direct central-bank access removes credit/liquidity exposure to a single commercial bank

- Preserves trade data confidentiality

The Swiss National Bank has interest-free intraday liquidity to repo CHF deposits with collateral, as do other banks for the purposes of liquidity management

Missed payments can cascade (one bank’s failure to pay USD in CLS could force counterparties to scramble for USD). CLS has loss-sharing agreements and central bank backstops to handle member failure, and indeed has managed past incidents (e.g. Lehman’s default in 2008) without losses to others.

Other quick facts:

- CLS is continuous linked settlement; a nonprofit company handling instantaneous settlement formed in 2002

- ATH volume of $15.4t in one day, ATH of 3.2m trades in one day. Average ~$7t/d in 2024

- Settles 51% of global FX transactions; only 18 currencies

- 17% of global FX volume are on currencies which are non-CLS tradeable source

- Most of this is RMB; 7% of global FX turnover

FX settlement risk is a focal issue. Approximately $2.2 trillion of daily FX turnover (nearly 30% of trades) remains settled without payment-versus-payment (PvP) protection, leaving participants exposed to counterparty default risk. Even including CLS, settlement risk in FX has grown in absolute terms, spurring calls for broader PvP adoption and new solutions (on-chain PvP?). Meanwhile, faster payment initiatives (e.g. SWIFT gpi) are improving post-trade processing and transparency of cross-border flows.

Other innovations

SWIFT gpi and Payment Reforms: While not specific to FX trading, the SWIFT gpi (global payments innovation) initiative has indirectly improved FX settlement transparency. gpi provides end-to-end tracking of cross-border payments and ensures faster credit (most gpi payments reach beneficiary same-day). For FX, this means when a trade’s currency leg is paid via SWIFT gpi, both parties can track it in real time, reducing uncertainty about payment status. Many banks have adopted MT 300 series confirmations and SWIFT gpi for FX, shortening the settlement cycles. Some markets are moving to T+1 or T+0 for certain trades (e.g. USD/CAD already T+1; India NDFs often settled T+0 in USD). The U.S. is shifting equities to T+1 in 2024, which means any FX associated (like USD to settle a foreign investor’s trade) also speeds up, increasing FX volume on short tenor.

Bilateral Netting and On-Us Settlement: Even outside CLS, banks mitigate risk by bilateral netting agreements – before settlement date, counterparties net all their payables/receivables in a given currency to one net payment. The BIS noted that presettlement netting reduced about $1.3T of gross payments per day in 2022. Banks also do “on-us” settlement: if two customers of the same bank traded FX, the bank can settle it internally on its books (no external payment needed). If those on-us settlements happen with proper controls (or internal PvP across accounts), risk is minimal. But the BIS pointed out some on-us settlements may not have full simultaneous exchange if not properly synchronized.

How does a neo-Fintech company (PSP’s, Wise, etc.) do FX?

TLDR; PSPs like Wise, Revolut and Stripe deliver low-fee, near-mid-market cross-border FX by matching flows locally, auto-hedging net positions and wiring via API-driven local rails.

When you send money A→B, PSPs either net against opposite flows in their regional accounts or hedge any net exposure in the interbank market. They run a pre-funded model (so there’s no customer credit), plug into open-banking and liquidity APIs, and trigger local payouts via Faster Payments, ACH, SWIFT gpi, etc.

FX Execution Models:

- Intraday & End-of-Day Netting PSPs group thousands of small customer flows into a single net position per currency pair—often on an hourly or daily cycle—then execute one wholesale FX trade to offset the net imbalance. This slashes both the number and value of trades sent to the interbank market, cutting execution costs and settlement risk

- Smart Order Routing & Algorithmic Slicing When netting leaves residual exposures, PSPs deploy smart order routers that split (“slice”) the remaining order into child orders, distributing them across multiple ECNs and bank APIs. Execution strategies like TWAP or VWAP help minimize market impact and aggregate liquidity across fragmented pools

- Real-Time Back-to-Back Hedging Some PSPs guarantee every customer conversion is immediately hedged: upon customer execution, an API call simultaneously executes an offsetting FX trade in the interbank market. This back-to-back model locks in mid-market price for the user and leaves zero directional FX exposure on the PSP’s books

- Dynamic Threshold Hedging PSPs set currency-specific exposure limits using a “one-day expected loss” framework and absolute risk appetites. Automated hedging engines monitor live net positions and trigger market trades as soon as thresholds are breached, keeping volatility risk within predefined buffers.

- Prime Brokerage & Multilateral Settlement At scale, PSPs forge prime-broker relationships and access CLS for PvP finality. They connect to multiple wholesale banks and ECNs, enabling them to internally match or externally hedge via prime brokers, and settle net positions through CLS to eliminate principal risk

Technology & Automation:

- Open Banking APIs to pull in customer funds instantly

- Streaming Liquidity APIs to source competitive FX quotes

- Automated Routing

- Check internal pools

- If short, hit the market

- Trigger local payout and ledger updates—all in seconds

Credit & Risk Management:

- Pre-funded model: customers pay first, so PSPs hold no receivable

- Fixed-rate windows: guarantee a quote for a few seconds/minutes

- Buffering: small spread built in to cover micro-volatility

Regulatory & Infrastructure:

- Licensed as EMIs or money transmitters (not banks)

- Heavy investment in AML/KYC screening tech

- Direct rails: Faster Payments, ACH, SEPA, SWIFT gpi (via sponsor banks)

- Optional CLS access for high-volume members to get PvP finality

Banks vs. PSPs:

- Risk appetite: PSPs avoid proprietary FX positions; banks often warehouse risk

- Product scope: PSPs focus on spot and simple forwards (SME forwards require collateral)

- Pricing: Near-mid-market + explicit fee vs. wider bank spreads & hidden markups

How do banks do FX?

Following 2008, there was a rule in the Dodd-Frank Act to reduce risky behaviour by banks and protect depositors — called the Volcker Rule, it prevents banks’ investment in hedge funds and private equity funds, but also prohibiting them from engaging in prop trading. Hence, the origin of PFOF.

Consider a corporate client wants to buy GBP/USD 50 million. The typical workflow:

- The client contacts the bank’s sales desk (via a platform or chat). At major banks, corporate and real-money flow is handled by a salesperson who interfaces with traders.

- The salesperson sees the request and may use the bank’s internal pricing engine to get a rate. Big banks have automated pricing for most standard trades up to a certain size: the engine takes in live market data (ECN prices, etc.), adds a margin based on client tier/size, and outputs a quote often in milliseconds. For very large or less liquid pairs, the salesperson will voice it to a trader on the FX trading desk.

- The bank executes the trade with the client at the agreed price. Immediately, the bank has an open position (long GBP, short USD in this example).

- Risk management: The trader (e.g. GBP/USD spot trader) will decide how to hedge. They might offset by trading with another client or on the market. If the bank has a flow internalization system, it might automatically match this client’s GBP buy with another client’s GBP sell (if one came in around same time). If not, the trader could go to EBS or another bank to sell GBP and square the position. Alternatively, the trader might choose to hold the position for a bit, speculating that price will move favorably (this is where the bank can make or lose money beyond the spread).

- Post-trade: The trade is confirmed, recorded in the bank’s systems. Back-office ensures settlement instructions go out (possibly through CLS if with another CLS member).

- Profit: The bank’s profit on that trade is roughly the spread charged plus any market move benefit when hedging. Dealers try to keep overall positions balanced but also take views. They operate under risk limits (e.g. a daily VAR limit, maximum open position in each currency).

Banks deploy pricing engines that stream quotes to various platforms (EBS, FXall, 360T, etc.) simultaneously. For instance, a bank’s eFX engine connects via FIX API to FXall to auto-respond to client RFQs within milliseconds, and to ECNs with limit orders or streaming quotes. Banks often have co-located servers near exchange matching engines for speed. They use quant models to skew prices depending on market conditions and internal inventory – e.g. if a bank is long a lot of EUR, its engine may shade the EUR offer price a tiny bit lower to encourage clients to buy EUR from it, reducing its inventory (this is called skewing or internalization bias).

How does Interactive Brokers do FX?

Major banks developed internal matching systems (internalization engines) to cross client flows internally rather than show every order to the market – this reduces information leakage and can give clients better fills. The BIS noted that a greater share of FX volume is being internalized or traded on “disclosed” relationship venues, rather than on the anonymous primary markets. This suggests that liquidity is plentiful but fragmented – no single venue has a majority market share; instead, dozens of venues and bank internal pools contribute.

To handle this, many institutions use aggregation software that pulls quotes from multiple sources (EBS, Cboe, Currenex, etc. for banks; or multiple bank APIs for a buy-side) and executes at the best price. Aggregators might also split a large order among venues. Smart order routing technology has thus become crucial in FX, akin to how equity algos route to different exchanges. Interactive brokers is one such venue.

Corporate Treasuries

Large MNC’s

Exposure Management

MNCs encounter a variety of FX exposures due to their global operations, which can be categorized into three main types:

- Transaction Exposure: This arises from specific, known cash flows in foreign currencies, such as a European subsidiary expecting a $10 million payment from a U.S. client in six months. Currency fluctuations could erode the value of this receivable if left unhedged.

- Translation Exposure: When consolidating financial statements, MNCs must convert foreign subsidiaries’ earnings into the parent company’s reporting currency (e.g., converting EUR profits into USD). A strengthening reporting currency can reduce reported earnings, even if operational performance remains strong.

- Economic Exposure: This is a longer-term risk, reflecting how FX movements affect an MNC’s competitiveness. For instance, if a competitor’s home currency weakens, they might lower prices, forcing the MNC to respond strategically.

To address these exposures, MNCs establish a formal FX risk management policy specifying:

- Which exposures to hedge (e.g., prioritizing transaction and translation risks over economic ones).

- Target hedge ratios (e.g., hedging 70% of forecasted cash flows within 12 months, tapering to 30% for 24-month forecasts).

- Approved instruments (e.g., forwards, swaps, or options).

- Execution guidelines, including delegation of authority and monitoring protocols.

For forecasted exposures, such as anticipated sales in a foreign currency, MNCs adopt a layered hedging approach. Hedge ratios increase as forecasts become more certain—perhaps starting at 25% for a 12-month forecast and rising to 80% as the date nears. For firm commitments, like a signed contract payable in JPY, MNCs often hedge nearly 100% to eliminate uncertainty, ensuring predictable cash flows.

Execution Workflows and Technology

- Treasury Management Systems (TMS): MNCs rely on platforms like Kyriba, SAP Treasury, or Reval to streamline their treasury operations. These systems allow treasurers to input exposure forecasts from subsidiaries, track positions in real time, and generate hedge recommendations. For instance, a TMS might flag a $50 million EUR exposure across multiple subsidiaries, consolidating it into a single hedge executed centrally.

- Multi-bank Platforms: To secure competitive pricing, MNCs connect their TMS to trading platforms like FXall, 360T, or Bloomberg FX. A treasurer might initiate a request for quote (RFQ) on FXall for a €50 million forward contract, receiving bids from five banks within seconds. Once a trade is executed, details flow back into the TMS via straight-through processing (STP), minimizing manual errors and enhancing efficiency.

- Bank Relationships: MNCs maintain relationships with a portfolio of banks—often 5 to 10 global players like JPMorgan, Citi, or HSBC—to diversify counterparty risk and ensure favorable terms. These relationships are formalized through annual bank mandates or requests for proposals (RFPs), where FX business is allocated in exchange for competitive pricing or credit support. Banks, in turn, provide credit lines for derivatives as part of broader financing packages, such as revolving credit facilities.

- Internal Netting: To reduce external hedging costs, many MNCs operate an internal netting center. For example, if a German subsidiary has a $10 million receivable and a U.S. subsidiary has a $10 million payable, the treasury nets these internally, hedging only residual exposures with external markets. Systems like Kyriba automate these netting cycles, typically monthly or quarterly, cutting transaction volumes and fees.

- Pricing and Benchmarks: MNCs demand transparency in pricing, often benchmarking bank quotes against WM/Reuters fixing rates (e.g., the 4pm London fix). For large trades, they might use fixing orders to execute at a specific rate, avoiding market slippage, or algorithmic execution to spread trades over time for optimal pricing. Tools like ITG or BestX provide transaction cost analysis (TCA), enabling treasurers to evaluate trade performance and negotiate better spreads.

Hedging Instruments

MNCs favour instruments that balance simplicity, cost, and effectiveness:

- Forwards: The workhorse of FX hedging, forwards lock in exchange rates for future delivery, ideal for firm commitments or high-certainty forecasts. For example, a forward might secure a USD/EUR rate for a $20 million payment due in six months.

- Swaps: Used to manage cash flow timing or roll over hedges, swaps are common when MNCs need flexibility in settlement dates.

- Options: These provide downside protection without obligation, useful for uncertain exposures like forecasted sales that might not materialize. A collar—an option strategy combining a put and call—might be used to lock in a budget rate, a tactic popular in industries like aviation where FX and commodity prices (e.g., fuel) are hedged together.

Platform Interactions

- Multi-bank platforms like FXall excel for competitive pricing on vanilla trades (e.g., forwards and swaps).

- Single-bank platforms are preferred for quick, small trades or when relationship banks offer tighter spreads on emerging market currencies (e.g., BRL or INR).

- SWIFT connectivity streamlines post-trade processes. Many MNCs join SWIFT’s SCORE network, receiving trade confirmations directly from banks and issuing payment instructions efficiently, reducing operational risk.

SME’s

- Unlike MNCs, SMEs rarely have ISDA agreements or multi-bank credit lines, limiting their ability to use derivatives or negotiate favorable terms.

- Historically High Costs: In traditional banking models, SMEs faced wide spreads—sometimes 200 pips on major currency pairs versus interbank spreads of 2 pips—due to their smaller trade sizes and weaker bargaining power.

Fintech-Driven Solutions

- Online Platforms: Companies like Wise Business, OFX, WorldFirst, and Revolut Business provide SMEs with spot FX and forward contracts via intuitive interfaces. These platforms often require pre-funding (e.g., depositing funds upfront) or a small margin for forwards, accommodating SMEs without established credit lines.

- Automated Hedging: Solutions like HedgeQuick or Kantox (acquired by BNP Paribas) simplify the process further. An SME inputs its exposures—say, $100,000 in expected USD revenue—and the platform automatically executes a forward contract based on predefined risk preferences, reducing the need for manual oversight.

- Simplified TMS: Traditional TMS providers like Kyriba have launched SME-friendly versions with basic features, while banks increasingly white-label fintech tools to enhance their SME offerings. For example, a regional bank might partner with Kantox to provide automated hedging to its clients.

Credit and Cost Considerations

While SMEs still face higher costs than MNCs, fintech competition has narrowed the gap:

- Spreads: Modern platforms offer SMEs spreads of 20-50 pips on minor pairs (e.g., USD/MXN) and under 10 pips on majors (e.g., EUR/USD) for moderate-sized trades, a vast improvement over the 100+ pips charged by banks historically.

- Credit Options: SMEs with solid financials might secure modest FX credit lines from banks, enabling unsecured forwards. Alternatively, they can use collared forwards (limiting upside and downside) or funded forwards (pre-paying a portion of the trade) to manage credit constraints, though these increase costs slightly.

Education and Advisory Services

Many SMEs lack the knowledge to navigate FX markets effectively, sometimes leading to risky decisions—like avoiding hedges based on market predictions. To bridge this gap:

- Educational Resources: Fintechs and banks offer webinars, guides, and calculators to demystify hedging. For instance, OFX might host a session on “Why Hedging Matters for SMEs,” illustrating how a 10% currency swing could wipe out profit margins.

- Many SME’s use speculative spot because they don’t know about forward contracts. One can buy forwards with a locked rate in order to hedge the date that they receive an invoice, for example. more details

Practical Example: Hedging with an NDF

Consider a small Argentine winery exporting wine to the U.S., expecting $500,000 in revenue in three months. With the Argentine peso (ARS) prone to devaluation, but the USD also volatile, the winery seeks to lock in its ARS proceeds. Using a fintech platform like WorldFirst, it books a USD/ARS non-deliverable forward (NDF). This contract sets a forward rate—say, 1 USD = 300 ARS—without physical delivery of ARS. At maturity, if the spot rate is 1 USD = 320 ARS, the winery receives a USD payout for the 20 ARS difference per dollar, securing its revenue in ARS terms. Such instruments, once inaccessible to SMEs due to complexity and cost, are now viable through fintech, typically costing a modest fee (e.g., 0.5% of notional value).

Existing crypto solutions

Projects like IBM’s World Wire and JPMorgan’s Liink/Onyx network have explored using blockchain tokens representing central bank money to do PvP for currency trades. The idea is to have tokens for each currency on a ledger and atomic swap them. Project Ion/DTCC and the BIS’s prototypes (e.g. Nexus and mCBDC Bridge) also target cross-currency atomic settlement using either central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) or tokenized deposits.

Fintechs like Baton Systems have built a platform to coordinate FX settlements. Baton interfaces with banks’ existing systems and uses a distributed ledger to allow participants to see trades, net them, and then synchronize payments through RTGS systems. Essentially, Baton overlays a PvP logic without needing a central entity like CLS – it orchestrates bilaterally. This can be used for currencies not in CLS or for participants that want flexibility. It’s reported that some banks are testing such systems for bilateral PvP on demand, potentially reducing trapped liquidity (since CLS has a single daily settlement window, whereas bilateral arrangements could settle multiple times per day).

My open questions

- There seems to be an obvious gap for “CLS but more open/democratized” but how do we actually appeal to eg. Xiaomi, which has its own CFO which presumably does payments/makes them more efficient?

- As an extension, what made Amazon use Stripe when they had their own solution already?

- How much money do they lose on not buying forwards for their inventory

- Devil’s advocate VC question: CLS is commoditized; why not us?

- Why aren’t more companies/users using CLS? It’s obviously better/cheaper; is it:

- bad incentives — banks can make money as is so they still price FX at 2.5% so they don’t lose their margin

- bad marketing — they don’t know it exists

- then: why does Wise not use CLS through its partner banks when it loses so much on hedging?

Insights

- Banks are at a fundamental disadvantage due to not being able to have a prop desk due to the Volcker Rule

Glossary

- PvP: Payment versus Payment; essentially an escrow service

- SMB/SME: Small-Medium Business/Enterprise

- MNC: Multinational Company

- PFOF: Payment for order flow

- Last Look: A liquidity provider, upon receiving a trade request, has a short window to accept or reject the trade if price moved or fails credit check. Meant to avoid stale pricing trade, but can be abused if misused.

- VaR: Value at risk

- NDF: Non-deliverable forward, OTC derivative to settle the difference between a forward rate and spot rate at a future date without delivery of the underlying currency from either party

References

- Bank for International Settlements – Triennial Central Bank Survey 2022’: Global FX volume and instrument breakdown; currency shares and trading center data.

- Reuters – “Global FX trading hits record $7.5 trln a day – BIS survey” (Oct 2022): USD in 88% of trades; RMB rising to 7%; London’s market share dip and Singapore’s rise.

- BIS Quarterly Review (Dec 2022) – _“FX settlement risk: an unsettled issue”_: ~$2.2T at risk daily, ~30% of deliverable FX turnover lacks PvP.

- Euromoney FX Awards 2024 – industry trends: CLS settlement averages $7T daily; 360T’s growth in swaps (NDF volumes).

- Global FX Code (2017, updated 2021) – principles on last look, information sharing.

- International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA) – guidance on Sustainability-linked Derivatives.

- BIS Innovation Hub – reports on multi-CBDC experiments (Project mBridge, Jura) demonstrating cross-border FX PvP with digital currencies.

- CFTC and ESMA regulations – various releases on FX forwards exemption, leverage rules for retail FX.

- Global Financial Markets Association and this – reports on FX market clearing and settlement improvements (advocating expansion of PvP).