I.

One of the recent Twitter outrages has been with seemingly ridiculous headlines of people making great money, top 1% or 0.1% incomes, yet feeling broke. Some along the lines of

Scraping By On $500,000 A Year: Why It’s So Hard To Escape The Rat Race

60% of millennials earning over $100,000 say they’re living paycheck to paycheck

$500,000 a Year Yet Struggling

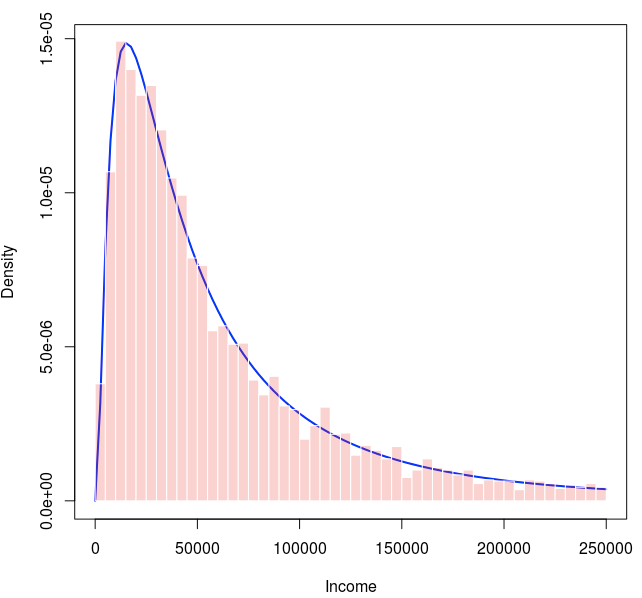

Anthony Lee Zhang proposes a statistical explanation that can be visualized via a distribution of income.

Consider the concept of a “social bubble,” a space inhabited by individuals who fall within a similar wealth distribution range, typically about 5-10 percentiles on either side of one’s own standing. For example, an individual in the median wealth bracket would interact primarily with those who fall within the 45th to 55th percentiles. This narrow wealth gap of just a few thousand dollars may appear insignificant, fostering a sense of relative wealth within their immediate social circle. This is largely due to the lower variance of wealth within this social bubble.

Contrast this to the individual in the 95th wealth percentile. They may perceive themselves as affluent, but their social interactions occur within the 90th to 100th percentiles. In this sphere, they are a millionaire surrounded by individuals whose wealth surpasses their own by several orders of magnitude. The disparity is striking; for every yacht owned by our hypothetical millionaire, their wealthier peers own ten. Despite being financially better off than most, they might feel inadequate due to the vast wealth differences within their social bubble. Here, the wealth variance within the bubble is significantly higher.

This phenomenon is largely attributable to the properties of a lognormal distribution, which has a much larger conditional variance in its right tail than near its centre. Thus, being positioned at the far right of the distribution means that a shift of just a few percentiles represents a vast amount of money, even in percentage terms.

Similar patterns may be found in other domains, such as sports and academics, where the distribution of ability often appears lognormal. For a mediocre tennis player, the abilities of their peers seem fairly homogenous, fostering a perception of general mediocrity. However, when their skill level brings them into proximity with someone like Federer, they suddenly become aware of the vast disparity in ability, causing a shift in perception and potentially feelings of inferiority.

II.

In 2009, then-Malaysian-Prime Minister Najib Razak established a sovereign wealth fund named 1MDB. The goal? To promote economic development. The actual outcome? A saga of corruption and embezzlement that would reverberate across the globe. With Razak at the helm and financier Jho Low pulling the strings behind the scenes, an intricate network of shell companies, illicit money transfers, and fraudulent financial deals was woven. Jho Low, a Harvard graduate with a penchant for high-rolling partying and lavish lifestyle, became the linchpin of the operation. The conspiracy began to unravel when in 2015, the Wall Street Journal reported that $700 million from 1MDB ended up in Razak’s personal bank account. Suddenly, the world’s attention was on this obscure Malaysian development fund, and as the layers were peeled back, the scale of the deception became evident. Billions of dollars from 1MDB were diverted through various channels, including shell companies and offshore accounts, and used for personal gain, luxury real estate, artwork, and funding extravagant lifestyles.

Yet, my biggest surprise was not the astronomical sums involved, but the staggering number of people lining up to bask in Low’s ill-gotten glory. Were they really so naive as to how he had gotten hundreds of millions of dollar’s in liquid funds? Or was it just none of their business?

Low’s circle included celebrities like Leonardo DiCaprio, Paris Hilton, Alicia Keyes, Jamie Foxx, Busta Rhymes, and Miranda Kerr, each of whom were paid princely sums to play the role of “friend”. Perhaps the most striking example of status-seeking behaviour came from DiCaprio, who managed to convince Low to almost single-handedly bankroll the movie, The Wolf of Wall Street.

What drew high-status individuals like DiCaprio and Kerr to orbit Low? It’s likely simpler: that despite their success, they yearned for more. Low, they believed, held the golden ticket to that realm of uber-elite status.

In our highly connected and interdependent globalized world, a new social issue emerges: no matter your status, there’s always another group just out of reach and plainly visible.

This is a surprisingly new phenomenon. In the past, being a big fish in a small pond—whether in a small town, a smaller country, your company, your friend group, or your private club—brought deep satisfaction and fulfilled a desire for a higher status.

In Canada, politicians show a similar trend. Traditionally, they would retire to peaceful lakeside cottages after leaving office. Today, they are more likely to join international consulting firms, using their political careers as springboards for future wealth and elite status.

This shift has troubling implications: politicians may focus more on preserving their post-office reputation and job opportunities rather than serving the public. After all, Canadian public service salaries, even at the highest levels, pale in comparison to large law firms. The lure of post-office opportunities might also attract a different, perhaps less service-minded type of individual to politics.

Canada’s lower industry salaries, especially in tech and law, are increasingly being compared to higher-paying American jobs. This contrast drives talent to cities like NYC, SF, and LA, draining local communities of their “indigenous” elite. Those who stay often feel underachieving, their success overshadowed by the grandeur of their southern neighbor.

Social media worsens this issue. Parents used to highlight local success stories. Now, they showcase the uber-successful from around the world. A two-week hiking trip seems insignificant compared to those who’ve hiked the Pacific Crest Trail. Even if you’ve done that, others have completed the Triple Crown of thru-hiking. Your Machu Picchu photo is just one among many. Your niche blog is overshadowed by the endless parade of Substacks from top authors. Every hobby is now subject to relentless global comparison.

Moreover, forming online connections with like-minded individuals diminishes the appeal of engaging with the local community. Why bond with your local running group when you can watch hours of content from a popular running vlogger?

In the past, we weren’t necessarily more stoic, but our limited exposure allowed us to feel content with our social standing. Today’s constant exposure fosters a sense of inadequacy, discourages local engagement, and creates a society more distinctly divided into haves and have-nots. As independence and loneliness rise and community attachment falls, these comparisons can only worsen.