The following was an essay I gave my mom to present my perspective and persuade her to support my decision to go from a gap year to dropping out of UBC indefinitely. Admittedly, many of the arguments are strawman and overly monetary.

I.

J gave me a valuable insight: the previous immigrant generation grew up in a scarcity mindset (a term coined in The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People) shaped by past hardships and uncertainties, focusing on conserving resources and viewing opportunities as limited. In contrast, an abundance mindset, emerging from stable and resource-rich environments, encourages risk-taking, innovation, and sees opportunities as abundant and accessible. A suitable mental model of this is thinking of reasons to join a new opportunity in terms of the worst case scenario (scarcity mindset), or the best case scenario (abundance mindset). I believe the majority of these arguments can be summarized effectively by this gap in worldview, and the resulting differences in agency, resourcefulness, and risk tolerance.

Today’s tech companies are more meritocratic than they ever have been, at every company size. Mom herself sent a news article mentioning Stanley Zhong, an 18 year old who was hired as an L5 at Google, and my current tech lead was hired by vk.com(Russian Facebook) at 14. Crypto is even more meritocratic. A friend is a research engineer at Paradigm, a venture capital firm and Blowfish’s lead investor, a sector famously known for ageism and credentialism; he’s 16 and was hired at 15. I despise it when others give a couple examples of people they know and extrapolate from it, so it’s worth a look into the rationale behind this: there are more ways to quantify skills than there ever have been. I am exceptionally thankful to be working in programming for this reason. Think you’ve got what it takes to be a data scientist? Compete against the best on Kaggle, with the prize being 5-7fig, alongside an inevitable flood of job offers. Are you a talented competitive programmer? Google, Facebook, Codeforces, and just about every big tech company runs competitions with a job as a prize. Think you’re good at security? Try out CTF’s, curta.wtf, or competitive audits; top competitive auditors make over $1m/yr. With this level of knowledge quantification, nobody cares if you were the president of the Solve Cancer And Erase Poverty Club in university. Nobody cares that you don’t exude an upper-class vibe; CEO’s regularly cuss. All that matters is: can you create value or not? Tech remains one of the few lucrative industries where individuals can still achieve success in this manner.

Let’s step back and look back even farther at why credentialism and postsecondary institutions exist in the first place. Griggs v. Duke Power Co. was a 1970 lawsuit which made it to the US Supreme Court in 1971. The ruling prohibited employers from using employment tests or educational requirements that were not directly related to job performance, especially when such practices disproportionately impacted minority groups. This led to a shift in employment criteria; employers sought alternative ways to assess candidates’ potential. This led to an increased emphasis on college degrees as a measure of ability and potential, contributing to a surge in demand for higher education. As more jobs started requiring degrees, there was a perceived need for higher education. This demand contributed to the expansion of colleges and universities and a shift in their role from elite institutions to more mass-market providers of education. It’s no coincidence the heightened demand for college education coincided with a huge increase in the rise in the cost of education. If an employer isn’t legally permitted to use the most reliable measure of intelligence that exists (IQ, which correlates with job performance at r=0.65 but also correlate highly with race) when hiring employees for cognitively-demanding positions, it will be limited to proxy indicators like colleges attended and degrees earned. This encourages credentialism and boosts the value of a college degree, thereby increasing the demand for undergraduate and graduate-level education, which gives colleges an opportunity to raise tuition costs faster than the overall inflation rate. The extra dollars brought in get increasingly pushed into peripheral administrative activities (like DEI) unrelated to the essential function of a university, and into boutique and heavily-ideological areas of studies. Traditionally, the recruitment processes of yore are intended to filter out candidates as efficiently as possible. To hire more people, a recruiter has a choice to either spend time reducing false negatives, or to simply draw another sample. Some amount of optimization is worth it, but in my experience, most people are way over-indexed on optimization and under-indexed on drawing more samples. This is especially true in recruiting at a big company. The cost of a false positive is much higher than the cost of a false negative. Firing someone is hard and takes months of managing them out, but after rejecting a worthy candidate, there are hundreds more. Startups have thrived taking advantage of this and finding the “diamond in a rough” candidates that large companies have found too risky to take on. But more recently there has finally been a push into a more meritocratic, holistic interview process at larger and larger companies — for years, big tech has used data structures and algorithms problems as a proxy for programming skill and IQ, but only after pre-filtering for degrees, etc. Quant firms now use brain teasers and puzzles that are even more G-loaded than traditional coding interviews. They’ve discovered that finding that top 1% or top 0.1% candidate is worth all this effort since, in software engineering that candidate is 10x or 100x more effective than the marginal candidate. I’m not convinced that I’d want to join a company that primarily values credentials; it indicates a certain level of bureaucracy and Goodhart’s Law in which a recruiter is trying to protect their own job by maintaining some level of plausible deniability over if a candidate underperforms; “How was I supposed to know they were woefully incompetent, they graduated from Harvard!” From my own personal experience, one of the companies I interviewed at prior also realized this. REDACTED initially gave me an offer in July 2022 and recently reached out again to say that their offer was always valid, even as they pivoted to a AI; their leadership told me that they realized that hiring smart, driven people was most important to them.

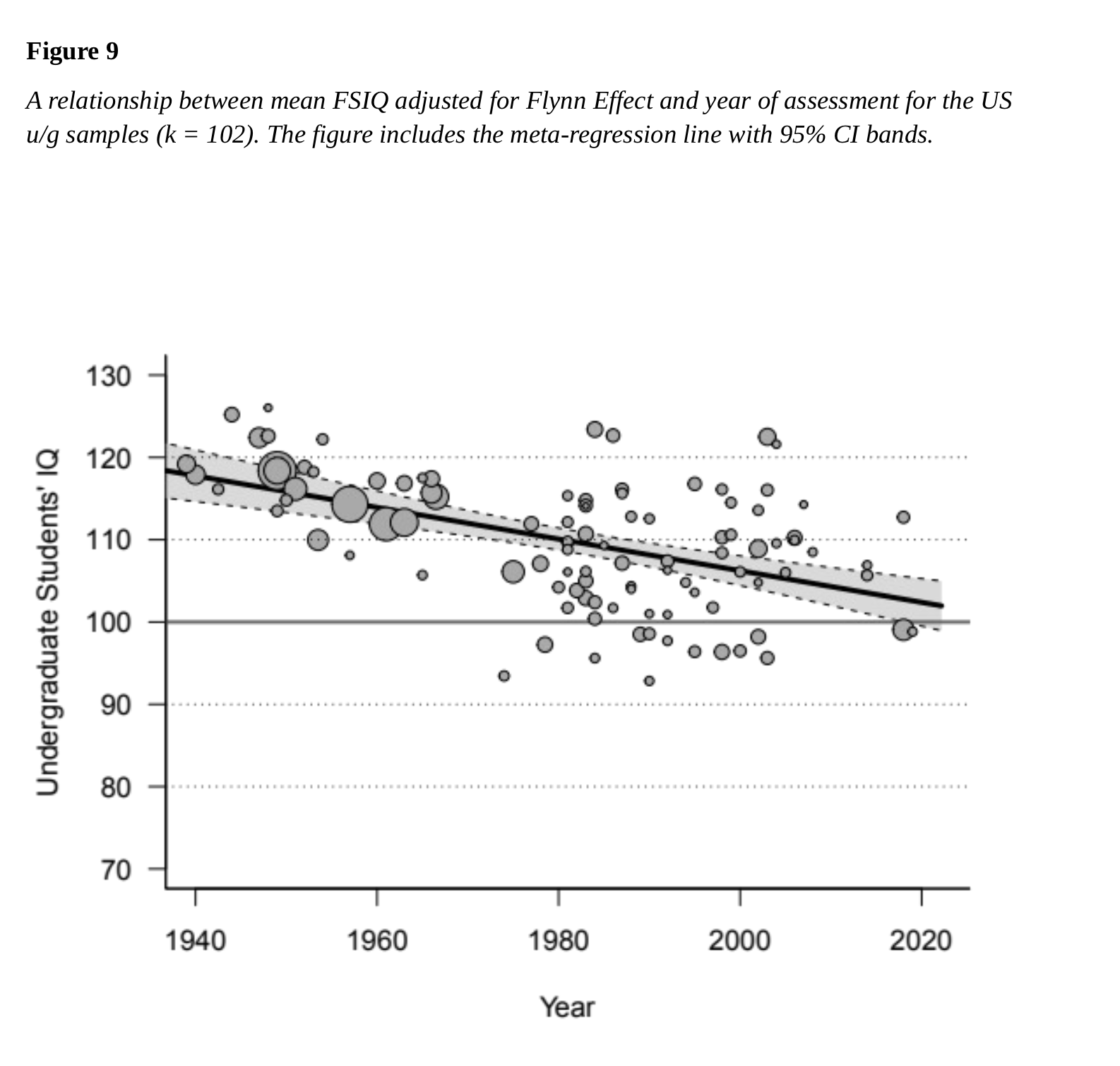

If pre-filtering for IQ is such a large component of the employment-finding value of a postsecondary education (whether or not it is conscious is a different argument), will it continue to hold up in the future? A recent meta-analysis of 106 undergraduate student studies found “the average IQ of undergraduate students today is a mere 102 IQ points and declined by approximately 0.2 IQ points per year (from 1939 to 2022). The students’ IQ also varies substantially across universities and is correlated with the selectivity of universities (measured by average SAT scores of admitted students)… Employers can no longer rely on applicants with university degrees to be more capable or smarter than those without degrees… Students need to realize that acceptance into university is no longer an invitation to join an elite group… Estimating premorbid IQ based on educational attainment is vastly inaccurate, obsolete, not evidence based.” It goes on to draw the conclusion that “the decline in undergraduate students’ IQ is necessary consequence of college and university education becoming a new norm rather than the privilege of a few. In fact, graduating from university is now more common than completing high school in the 1940s or 1950s.”

The paper provides useful insights into the reasons for this; among them, the Flynn effect, increased educational attainment, and others. The value of these findings and its implications on the future are left to the reader. Whether the selection of postsecondary credentials is due to IQ is open to speculation; but it seems if there was ever a time for decredentialism, it’s the present.

II.

The majority of my present successes hinge around a singular invention: my generation is the first internet native generation. While I was in school, I always wondered why the world’s singular best teacher at a class did not dedicate a significant amount of time to perfecting a definitive course on it. Some teachers just taught a small area of their profession extraordinarily well, perhaps a different way of explaining a single class that they do better than anyone else in the world. For example, Sviatoslav Richter produced the definitive recording of Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2 in C Minor. He put years of practice into perfecting a singular piece, and now is the gold standard for the world to enjoy in perpetuity. Why isn’t education the same way? More recently, there has been significant process made in this front; 3Blue1Brown has made the definitive series on linear algebra and other math topics with slick graphics and astounding content density. Hundreds of hours go into optimizing a singular video, which just isn’t possible for a normal teacher. For many fields it’s hard to just yolo into them, namely hard sciences, but even then everything is learnable online; many of my previous classmates say that they learned more from online sources than their own lectures during university. A friend was previously a chemist; when he enrolled in university, he started frequenting chemist forums, and by the time he graduated, his papers had more citations than any of his professors; and chemistry is a notoriously difficult subject to autodidact. A common argument against this would be “but you need top 1% agency”. And I would agree, but if you’re the type to yawn and watch Netflix after your 4 year degree, you’re probably not going to “make it” with that degree anyways.

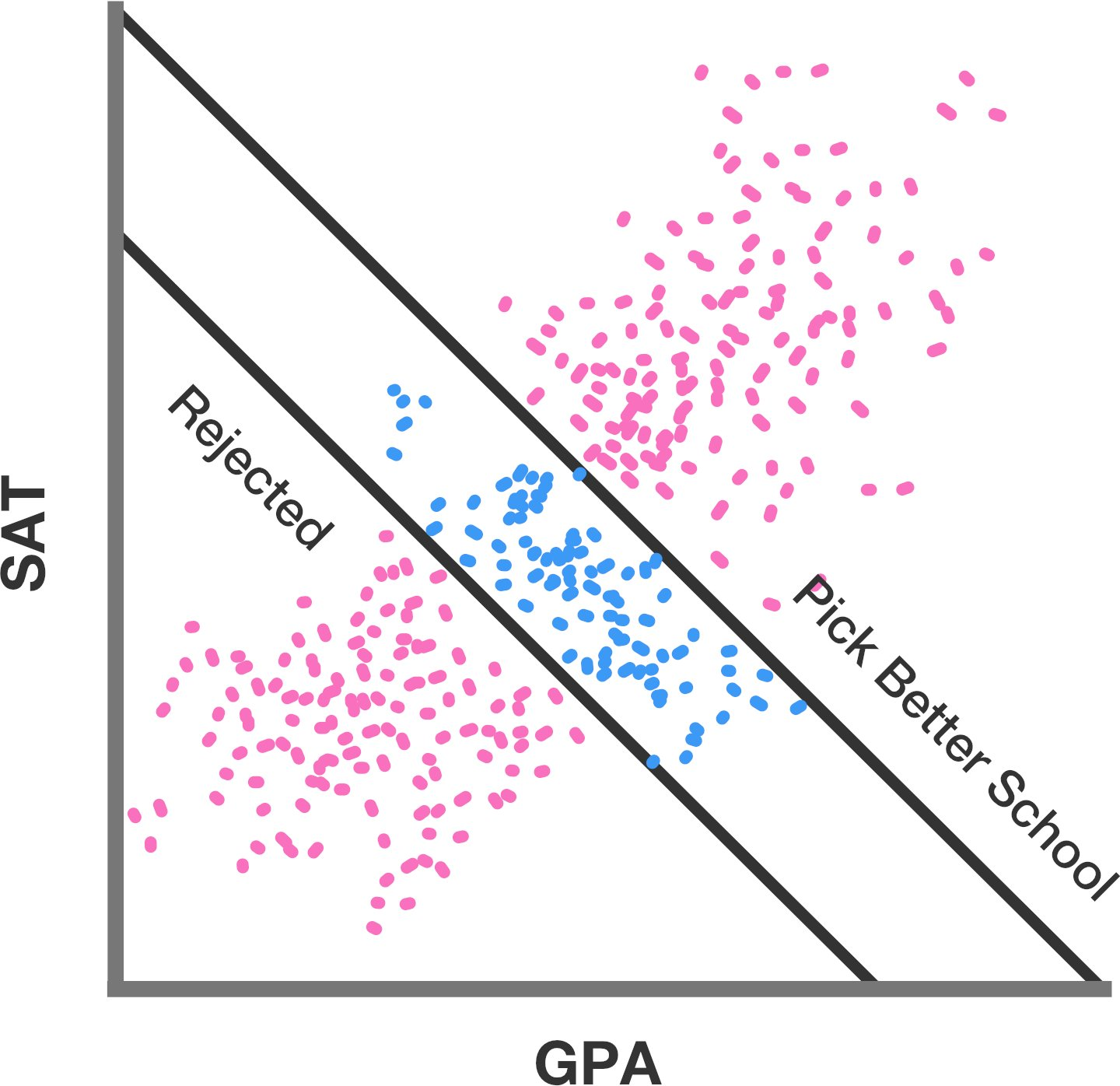

It would have been impossible for me to self-teach to my level without the internet, but I can also attribute my career success to tech-centric social media. Quite frankly, whenever an adult mentions “networking”, I feel that it’s a word they throw around to bullshit me into thinking there’s some secret sauce in meeting people at college that I can’t get anywhere else. Here’s an unpopular opinion: meeting others over social media is superior to almost every university’s “network”. A lot of the network-building a university promotes is by pre-filtering class, field, and arguably to some degree, intelligence through high school performance. But for all but the world’s best university, this filter applies as a ceiling too. I’m simply not going to find MIT-tier people at UBC; Peter Zhou, Canadian IOI gold medallist is attending to MIT, and similar individuals are above the ceiling of a “good but not great” university.

Perhaps slightly crudely illustrated by this graph:

On the other hand, being online is classless; Twitter doesn’t put a ceiling on the individuals one can interact with, and the pre-filtering is only agency; you have to really want it. There is no course on how to do Twitter well, nor parents telling their unwilling kids to do it for job prospects or such. Yet, one would be surprised how there are genuine friends in high places to be made and how easily accessible they are. I’ve played this game and still have much room to improve; it’s one huge reason I can get referrals. I already have a reputation built and interviewers either already know who I am, or can get a solid taste of my values through scrolling my feed. Interviewing at REDACTED, the recruiter told me I had many fans, and indeed, a few REDACTED engineers were followers. This is a superpower that previously wasn’t possible, enabling more serendipity than ever before.

III.

The statistical argument for university has historically been true, comforting millions of upwards-mobile households into thinking that anyone with a degree has it figured out. I’ll make a contrarian claim: that population-level statistics are very useful and powerful for research purposes, but are not nearly as interesting for someone personally. How can this be?

Consider the concept of income inequality: children from wealthier families generally have better life opportunities compared to those from poorer families. It’s important for a researcher to understand this as a true fact; if the scientific community ignored the advantages of being born into wealth, it would be a serious failure. Recognizing that wealth tends to stay within families is essential to grasp even the basics of how society functions. Denying this fact for political reasons would lead to such confusion that it might render one’s perspective on the world utterly meaningless.

But from a personal point of view, coming from a less affluent background is tough, but shouldn’t lead to despair. It doesn’t mean that a child from such a family should view themselves as destined to fail and not worth the effort to try to succeed. Despite being at a disadvantage, this isn’t new information and certainly isn’t something a child wouldn’t already feel without scientific confirmation. If a child were to obsess over every financial detail of their parents as if it sealed their own fate, they would be placing too much importance on these studies.

How does this translate to aggregate studies on postsecondary graduate income? The majority of short, memorable statistics on the topic are medians, for example “in 2021… the median earnings of those with a bachelor’s degree ($61,600) were 55 percent higher than the earnings of those who completed high school ($39,700).” from IES.

This ignores a lot of important factors. For one, the sampling bias of who goes to university; in the same way that every map is the same map, college attainment correlates highly with other statics (household income, etc.) That is to say, it’s less so a causation of income. It’s a population that conglomerates many negative early-life outcomes, and simply membership to such a heterogeneous group doesn’t indicate one will be a low earner. More importantly, both of these populations are extremely high variation; a high school graduate could be someone just scraping by with passing grades, or Bill Gates.

A Manhattan Institute report on US Census data looks into “crossover points”: the percentile a HS graduate must be to overcome a certain percentile of BA holder. If, for instance, the highest-income 25% of workers with only a high school education earned more than 50,000, the crossover point would be 25. Higher crossovers mean more overlap; a crossover point of 50 means that both groups have the same median. Nationally, the crossover point between HS and BA is 33.2; meaning that even with the sampling. In particular, high school–only workers who reach the top of their earnings distribution often do so in occupations where entry-level positions offer a pathway to advancement.

This is all ignoring my own personal situation; there exists a population far above the crossover point such that a postsecondary education costs more in opportunity cost than it’s worth in future earnings. No statistics exist for such a crossover point due to its rarity, and it differs from university to university; future earnings at a prestigious school likely outweigh even the most outlier 18yo’s achievement. However, I believe my opportunity cost crossover point is above that of my prospects of UBC.

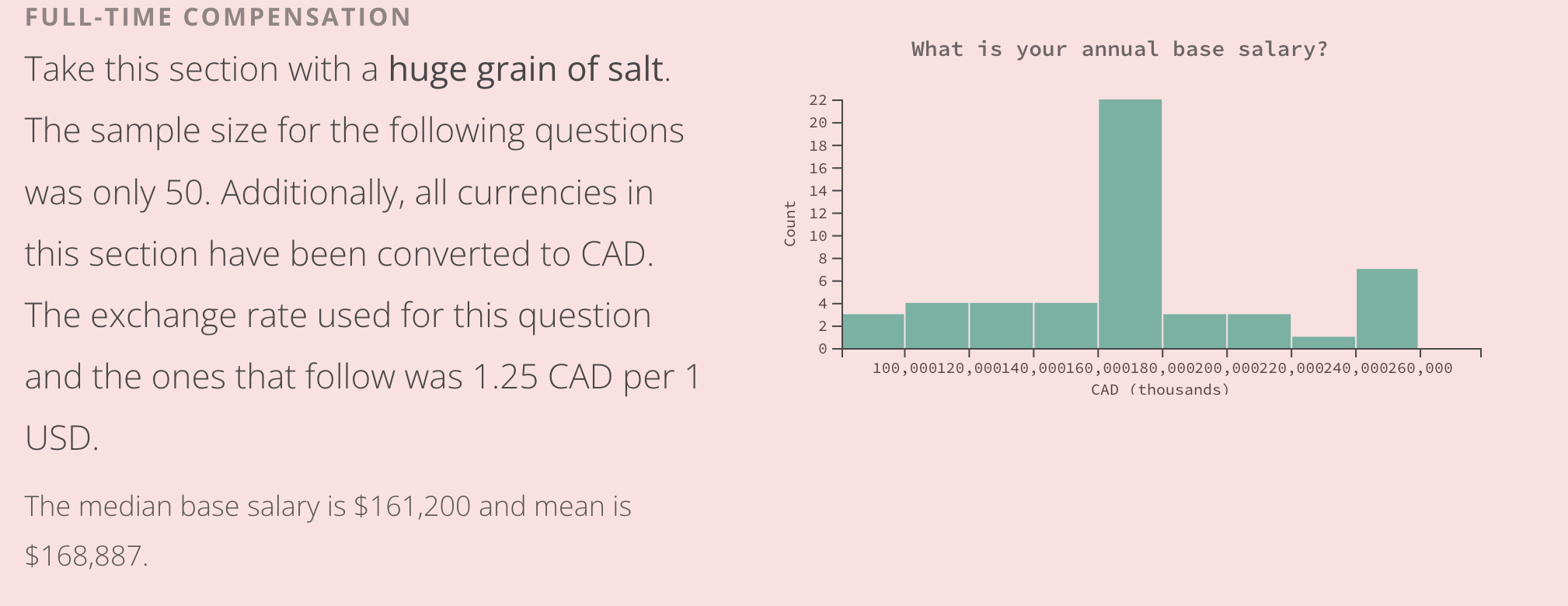

Even the best outcomes from Waterloo’s Software Engineering 2022 Class Profile struggle to justify their opportunity cost.

IV.

Academics view their comparative advantage fundamentally as arising from field-specific knowledge, whereas (a subset of) business types tend to view their comparative advantage as arising from work ethic, “cleverness”, and other such general skills. Business types are relatively happy to adopt new tech - crypto, LLMs, etc. They are very happy playing on level playing fields, because the assumption is their high general ability will help them win if everyone is at the same starting point. The stereotypical academic, on the other hand, is valued because of a body of knowledge built up on existing topics. The advantage is in the familiar. Anything too novel threatens to dilute this advantage. It’s tempting to reject the new, which one could attribute to a kind of fear: fear that the new represents an area where the source of the academic’s comparative advantage is highly diluted. The scrappy business type thinks exactly the opposite: where the advantage is general ability, any levelling of the playing field is beneficial. Chaos is a ladder. In greenfield tech, nobody really knows anything. It’s a feeling that’s hard to describe, but one that makes working in tech, and particularly startups, so indescribably rewarding.

If there’s something we agree on, it’s that doing something for the purpose of others is a great way to have regrets. It’s how I feel about university; there’s so many rational reasons for me not to go back, and few reasons for it: “oh my mom told me to” (among social reasons).

Frequent counterarguments (and my response)

“What if you get fired/crypto goes to zero/everything dies”

Then I concede defeat, and go back to university as a more mature, experienced, wise person. The choice not to attend university is a two-way door; it is reversible with minimal effort. I’ll continue to reapply to UBC every year, and they’ll continue to accept me. It’s a nominal fee for a year of “insurance”, such that I can always return to university if I so please.

”Startup employees don’t make much upon an exit”

I’m sad M says this since it probably means he got screwed in some way in the past, or maybe it’s that oil and gas companies don’t give nearly as much equity as tech startups to early employees, or don’t get acquired for much. This seems to be more a figment of salary negotiation than anything; a founding engineer in tech is usually compensated in such that any whiff of an exit nets a large sum.

”You’ll get fired as soon as a big company acquires you”

I never knew about this, so it’s useful knowledge, but it isn’t a problem to me. The EV of working at bigco’s doesn’t make sense at this stage in my life — there’s too much bureaucracy, too narrow learning, and not an asymmetric upside like startup equity. I’d likely quit within the year anyways, and getting fired with the excuse of “you don’t have a degree” is just free money in severance. I’m willing and able to put in the work for a startup at this point in my life, so that’s what I’d stick with for the time being.

I don’t think this is remotely the norm in tech companies either — in crypto, acquihires are more common than acquisitions for products. The people working for a company are more valuable than the company they’re acquiring, and hence contracts are structured as such (vesting of acquired shares); they wouldn’t even think about firing the employees they just spent millions on.

”You’ll learn the cutting edge, newest fields at university”

Consider the incentives and value capture of being a professor vs being in industry. Doing cutting edge research at a university has absolutely zero asymmetric upside; not to mention that top researchers are rarely prolific lecturers, let alone to an undergraduate classroom. Sure, one can point to the many unicorns founded by academics (Google, Sun Microsystems, and Intel come to mind), but they would never have been professors during the time. These days, academia is woefully behind on many topics; there isn’t a worthwhile blockchain class outside of Stanford, and it’s likely that there will never be another academic state of the art LLM, ever.

There are definitely genius professors; the likes of Geoffrey Hinton, Richard Sutton, etc. but they are moreso diamonds in the rough, rather than the norm that cutting edge fields are advanced by academia instead of indusrty.

”People like us do things like this”

Please see, or this; mimetic desire is not a rational argument.