this was initially a position paper for a long-winded discussion on meritocracy with a few friends; an amalgam of many existing blogs/articles i’ve read over the years.

I.

In sociology, there is the concept of the three major perspectives, two of which are of interest. A cliffsnotes article summarizes it into this chart:

| Sociological Perspective | Level of Analysis | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Functionalism | Macro | Relationship between the parts of society; How aspects of society are functional (adaptive) |

| Conflict Theory | Macro | Competition for scarce resources; How the elite control the poor and weak |

This is a drastic oversimplification of the world of political meta-theory, that is to say theories about why different political ideologies and political conflicts exist. Functionalists believe that political disagreements exists because of inherent conflicts of politics; if we all understood the evidence better, we would agree on more. For functionalists, politics is not a zero-sum game, but rather, a process of growing the pie so that there is more of the pie to take for everyone. Conflict theorists treat politics as war, where different factions with competing interests are in constant battles to determine whether the State enriches the Elites or helps the People. This isn’t a leftist or a rightist idea — perhaps the horseshoe theory, that hard-left meets hard-left, is true in this case. They are equally more amenable to conflict theories than the generally more functionalist centre. Both soft-left and soft-right do ever-so-often dabble in conflict theory in some issues, notably taxation being good for the community as a whole, “1%” vs “99%"", or “chronic welfare recipients” vs “hardworking Americans”.

Functionalists treat politics as a startup. The State is floundering, and we are all trying to play our small part in nurturing it back to success. Engage in discourse. Some have good ideas, others have bad ideas, some are 10x engineers, others propose plans with too many unintended consequences. Some of these plans may get implemented — “Fuck around, find out”, as they say; mistakes happen.

Conflict theorists prioritize the inequality between opposing groups as their primary concern. The Elites, although fewer, possess substantial wealth and power, while the People, despite being numerous, are economically disadvantaged but possess unwavering determination and sincerity. The Elites aim to create discord and bewilderment, whereas the People must strive for unity. The outcome of political struggles hinges on the effectiveness of each side’s strategic execution.

Functionalists see open dialogue as crucial. Each of us brings unique expertise and perspective to the table, and by collectively assessing the situation, we can leverage the wisdom-of-crowds to arrive at the most suitable action plan for our shared client, the State. The outcome on any specific issue is less significant than fostering an environment where accurate assessments and effective solutions consistently triumph over time.

Conflict theorists see debate as playing a limited role in providing clarity at best. Engaging in a “debate” with your supervisor about receiving a raise occurs with the mutual recognition that both parties have inherently conflicting interests, and the “winner” depends less on objective moral principles and more on the balance of power. If your boss frequently cites objective moral principles, they are likely presenting an unfavourable offer.

Functionalists focus on the complexities and unintended consequences of social engineering. They point out that anti-drug programs in schools may increase drug use, raising the minimum wage could hurt the poor, and executing criminals can cost more than life imprisonment. Consequently, they argue that policy decisions should be based on extensive research, debate, and reliance on scientific authorities, rather than relying on intuition or simplistic solutions.

Conflict theorists argue that such complexities often serve as convenient excuses for maintaining the status quo. They highlight the stark disparities between the wealthy elites, who continue to amass fortunes, and the struggling masses, who face hunger and destitution. Conflict theorists contend that when calls for wealth redistribution arise, elites manipulate information and spread fear to prevent any progress toward economic justice, leaving the masses in a perpetual state of deprivation.

Functionalists believe that increasing intelligence can save the world. They advocate for highly skilled technocrats who can develop optimal policies, competent politicians who can choose the right experts and implement their recommendations, and well-informed voters who can discern and elect the most capable leaders.

Conflict theorists argue that fostering passion is the key to changing the world. They emphasize the need for the poor and powerless to unite and advocate for their rights, with committed activists raising awareness, community organizers forming labor unions and youth groups, and protesters mobilizing rapidly to counteract any deceptive tactics. For conflict theorists, it is crucial that voters consistently participate and discern which candidates genuinely represent their interests.

Functionalists, however, view passion as insufficient and potentially detrimental. They argue that loud, misguided voices can disrupt rational debates and introduce bias. For example, if an emotionally charged group influences a medical diagnosis through protests, they undermine the essential process of informed analysis and discussion, leading to potential harm.

Conflict theorists see intelligence as inadequate and sometimes deceptive. They argue that common sense is enough to understand the injustices faced by underpaid workers in harsh conditions, while highly intelligent individuals might use their knowledge to present misleading arguments that prevent necessary changes from being implemented.

II.

Liberalism’s primary focus is peaceful coexistence, with liberty, fraternity, and equality as its main tenets, corresponding to the grey, red, and blue tribes in U.S. politics. However, the term “liberal” has become associated with anti-liberal sentiments like Marxism due to shared goals with liberal distributive egalitarianism. This is a generalization that claims that Marxists don’t consider the hard, technical problem of how to design good government. Yet, it does explain why their governments fail so often, and why whenever existing governments are bad, Marxists jump to the conclusion that they must be run by evil people who want them to be intentionally bad.

A position for functionalism is as simple as examining one’s thought of the other. Functionalists think conflict theorists are simply making a mistake. On a fundamental level, conflict theorists don’t embrace Hanlon’s Razor, to “never attribute to malice what can be explained by stupidity”, stuck at some glowing-brain meme where they think forming mobs and smashing things can motivate decision makers to solve incredibly complex social engineering problems.

Conflict theorists tend to view Functionalists as adversaries in their struggle; they may be directly affiliated with powerful entities like Big Tech. More fundamentally, however, they are perceived as part of a class prioritizing the preservation of its privileges over the welfare of the poor or the common good. At best, they may strive to maintain neutrality, oblivious to the fact that neutrality often favours the powerful in conflicts between the powerful and powerless. Thus, the appropriate reaction is to confront and challenge them.

I’ll give you a one-sentence TL;DR here: This argument could be summarized as a {doctor, engineer, etc} angrily yelling “Did you even read the documentation before you inflicted your idiotic opinions on us?!” And since I’m one of the engineers often yelling this exact phrase, my position is rather obvious; I adopt functionalism, taking political problems as outgrowths of bias and irrationality, that to those figuratively wearing a crown, every issue is one of cognitive bias or irrationality. Certainly “everyone in government is already a good person, and just has to be convinced of the right facts” is looking less plausible these days. But I believe that embracing the conflict perspective in politics often leads individuals to adopt a more pragmatic attitude. When society is characterized by the interplay of influential factions, it encourages a sense of skepticism. Persistent social conflict, which can be harsh and occasionally deceptive, shapes one’s political outlook, resulting in a more somber worldview.

What would the conflict theorist argument against this essay be? Is it similar to this, an explanation of conflict theory against functionalism, and a defence of why conflict theory explains the world in a better way than functionalism does? This is an open question to any conflict theorists. Oh wait, we actually have a ton of conflict theorists opinions in the media, because that is what gets clicks. This one somehow attempts to argue that public choice is racist, and if you believe it, you’re a white supremacist. If you did not predict this, you do not understand the fact that conflict theorists aren’t just a functionalist who disagrees on what the mistakes of society are.

III.

Vox calls for an attack on the false god of meritocracy. The Guardian says down with meritocracy. Prospect writes about the problem with meritocracy. There’s even a book called The Meritocracy Trap and Against Meritocracy. Given meritocracy sounds tautologically good — after all, it just means positions should be going to those with the most merit — there are a surprising number of people against it. In fact, the term “meritocracy” was initially coined as a negative term in a dystopian science-fiction novel criticizing streaming in British schools. (yes yes, wikipedia as a source, no, I don’t care.) It subsequently was adopted as a positive term, which the author in question rather disliked.

This is the media after all, so some of these are obvious clickbait. Some argue that meritocracy would overall be positive, but we haven’t reached it yet (which I would agree with, although the title seems to suggest otherwise). But some of them really mean it — that a perfect meritocracy would be undesirable. Their arguments centre around this idea that elites send their children to private schools, where they score 1600 on the SAT, become president of the Solve Cancer And Erase Poverty Club, attend Harvard Business School, and impress their professors. They are then hired by Chase-Citi-Fargo-Goldman-McKinsey-Morgan-Barclays-BCG, spending their days eating flavoured caviar and chatting to their friends about how they deserve their positions out of merit. Then, they repeat the cycle with their own children.

I’ll admit — none of this is false. Does this should mean we should be opposing meritocracy?

IV.

The common argument for these meritocracy-hating articles is that meritocracy is founded on the belief that smart people deserve good jobs and therefore money, as a result of being smart. To quote “The Tryhards”,

I reject meritocracy because I reject the idea of human deserts. I don’t believe that an individual’s material conditions should be determined by what he or she “deserves,” no matter the criteria and regardless of the accuracy of the system contrived to measure it. I believe an equal best should be done for all people at all times.

More practically, I believe that anything resembling an accurate assessment of what someone deserves is impossible, inevitably drowned in a sea of confounding variables, entrenched advantage, genetic and physiological tendencies, parental influence, peer effects, random chance, and the conditions under which a person labours. To reflect on the immateriality of human deserts is not a denial of choice; it is a denial of self-determination. Reality is indifferent to meritocracy’s perceived need to “give people what they deserve.”

This statement is simultaneously accurate (particularly that more intelligent individuals should not be inherently more privileged), and yet overlooking the main issue. The fundamental idea of meritocracy lies in the following scenario: if you require a complex surgery to save your life, would you choose a surgeon who excelled in medical school or one who barely passed through additional training with a C-? If you opt for the former, you advocate meritocracy in terms of surgeons. Broaden this concept slightly, and you have the rationale for supporting meritocracy in all other careers.

The difference between the Federal Reserve making favourable or unfavourable decisions can result in an economic surge or a downturn, affecting the livelihoods of ten million workers who may either receive raises or lose their jobs. Given the high stakes, it is crucial to have the most competent decision-maker – meaning that the selection of the Federal Reserve’s head should be based on merit.

This issue is not about fairness, deservingness, or any other related factors. If wealthy parents invest in experimental gene therapy for their unborn child, resulting in the child becoming an exceptionally gifted economist without any personal effort, then I would want that individual to lead the Federal Reserve. If you’re concerned about preserving the jobs of ten million people, you would agree.

V.

”Oh no sudo, you’re sucking it up to the truffle-eating, Harvard-educated elite at Chase-Citi-Fargo-Goldman-McKinsey-Morgan-Barclays-BCG?” I hear you say. Not at all, the simple solution to this problem is one that none of these anti-meritocracy articles dare suggest: education, merit, and intelligence are all distinctly separate.

I am a specimen of this, as a High School graduate who is neither smart nor well-educated, working a full time software engineering job. I made sacrifices in other aspects of my life to get to this point. Again and again I read the same line from job descriptions: “Postsecondary degree necessary”. Some of those in a similar situation were less fortunate with their choice of field, or perhaps too poor to go to college, others afraid of failing. Some of these individuals go to college later in life, and rise up to the top. These people are not without merit. In a meritocracy, they would be up at the top, but in our society, they are stuck.

These days, college admissions is at the front of countless newspapers, many arguing how they are too meritocratic by gating based on achievement, SAT, and high-school class rank. They argue, among other points, that these factors are not correlated with college success. I agree with this, but to an extent far beyond admissions; success in college too only correlates weakly with “success” in the real world. Today’s doctors only got into med school because their undergraduate GPA (of an often-arbitrary major) was above a certain threshold in comparison with their peers. Perhaps an individual with mediocre college grades possesses the right skills to excel as a nurse, firefighter, or police officer. Unfortunately, we may never know, as all three professions are progressively basing acceptance on college achievements. Ulysses Grant, who graduated in the lower half of his West Point class, proved to be the only person capable of defeating General Lee and securing victory in the Civil War after a series of seemingly more qualified generals fell short. If a contemporary Grant exists, possessing subpar grades but exceptional real-world combat skills, can we trust that our current education system will identify him? Are we certain it will even make an effort to?

Perhaps the most amusing illustration of this point is chess. Chess has a mere r=0.24 correlation with the scientific pinnacle of G-measures. Kasparov has an IQ of 135 — my elementary/junior high classrooms had a higher average IQ than Garry Kasparov, yet I can say with certainty that none of the thirty-odd students in my class will ever have nearly the same success. If Kasparov’s academic achievements were solely based on his IQ, he may or may not have been admitted to Harvard, and he definitely wouldn’t have been their top student. Furthermore, if only this type of academic success determined eligibility for a national chess team, Kasparov and numerous other grandmasters would never have had an opportunity. Genuine meritocracy emerges when you disregard academic credentials and focus on who can truly excel in a chess match.

I am exceptionally thankful to be working in tech. I constantly rave about the quantifiably of developer skill (among other tech-adjacent careers). Do you believe you are a skilled data scientist? Compete against the best on Kaggle, with the prize being $1m, alongside an inevitable flood of job offers. Are you a good competitive programmer? Codeforces will offer you the same. Nobody cares if you were the president of the Solve Cancer And Erase Poverty Club. Nobody cares that you don’t exude an upper-class vibe, and CEO’s regularly cuss. All that matters is: can you code or not? My previous tech lead was a Russian developer who joined the Russian equivalent of Facebook (vk.com) at 14 and lead a team developing an 8-million-user app by 16. My previous CTO learned programming via magazines as a teen. Programming remains one of the few lucrative professions where individuals can still achieve success in this manner, and it’s not surprising that the establishment consistently depicts its culture as singularly malevolent, calling for its dismantling. I’ve long been a proponent of the opposite — more widespread quantification of skill, although I do acknowledge that technical STEM and individually comparative fields are more suitable for such methods. Rather than Goldman Sachs recruiting top performers from Harvard, they should employ individuals who can showcase their understanding of investment principles or, preferably, demonstrate a capacity to forecast market trends more accurately than mere chance. Among these people, some will be the academic prodigies who honed their skills at Harvard Business School. However, many others will be average working-class individuals who engaged in self-study or possess a natural talent, akin to the investment counterparts of General Grant and Garry Kasparov — perhaps the next George Soros.

I do not believe the authors of the anti-meritocracy articles mentioned truly disagree with this perspective. They likely employ an alternate definition of meritocracy, equating it to “governance by highly educated individuals with esteemed credentials.” However, it is crucial to defend the term “meritocracy” for its original meaning — decisions based on merit rather than wealth, class, race, or education — and as a positive concept. If we allow the term to be tainted as a vague representation of a corrupt system, it becomes all too easy for those entrenched in such corruption to exploit the deterioration of the only term that signifies an alternative. “Oh, you disapprove of essential positions being awarded to the upper class rather than those who excel in them? You’d prefer allocation based on merit? But haven’t you read The Guardian and Vox? Advocating for so-called ‘meritocracy’ is completely out of fashion!” Consequently, we risk losing one of our few rallying points and a crucial piece of vocabulary to articulate the flaws in the current system and suggest a better alternative. We must resist redefining “meritocracy” as “positions granted to individuals based on their class and ability to attend Harvard” and restore its intended meaning — positions being awarded to those who are most skilled and can best utilize them to benefit others. That is, after all, our ultimate goal.

This does not address one of the primary concerns raised by opponents of meritocracy: the existence of a disparity between affluent Goldman Sachs analysts and the impoverished. My argument is solely that, in a world where roles such as investment bankers, surgeons, or Federal Reserve chairs must be filled, I would prefer to select candidates based on genuine meritocracy rather than any other criteria.

VI.

My perspective as a functionalist is that governments exist to devise solutions to problems. Effective government officials are those who can identify and successfully implement these solutions. Consequently, we seek individuals who are intelligent and proficient. As meritocracy promotes the brightest and most competent individuals, it is axiomatically accurate. The only possible issue arises when errors occur in evaluating intelligence and competence, which is the focus of the remainder of the essay.

From a conflict theory standpoint, this argument lacks validity. Competent government officials are those who prioritize our class interests over their own. In the best-case scenario, merit has no correlation with this. In the worst-case scenario, we belong to the lower and middle class, while they represent the upper class, and a system (such as Ivy League universities) disproportionately channels the most deserving individuals into the upper class. Consequently, when we place the most meritorious individuals in government positions, we inadvertently populate the government with upper-class individuals who cater to upper-class interests.

Sidenotes on the Chinese Communist Revolution

This was a passage that I left out of the body since it didn’t belong in any singular section. Nonetheless, it’s an interesting thought and worth sharing.

Even if we assume the argument that intelligence = merit, intelligence is likely much less heritable than you likely believe. One meta analysis of an identical twin study over fifty years concluded (albeit with some significant error) that there is 17% direct heritability of intelligence. There’s also the long-established trend that monetary success is inversely correlated with birth rates which likely more than compensates for this heritability of intelligence.

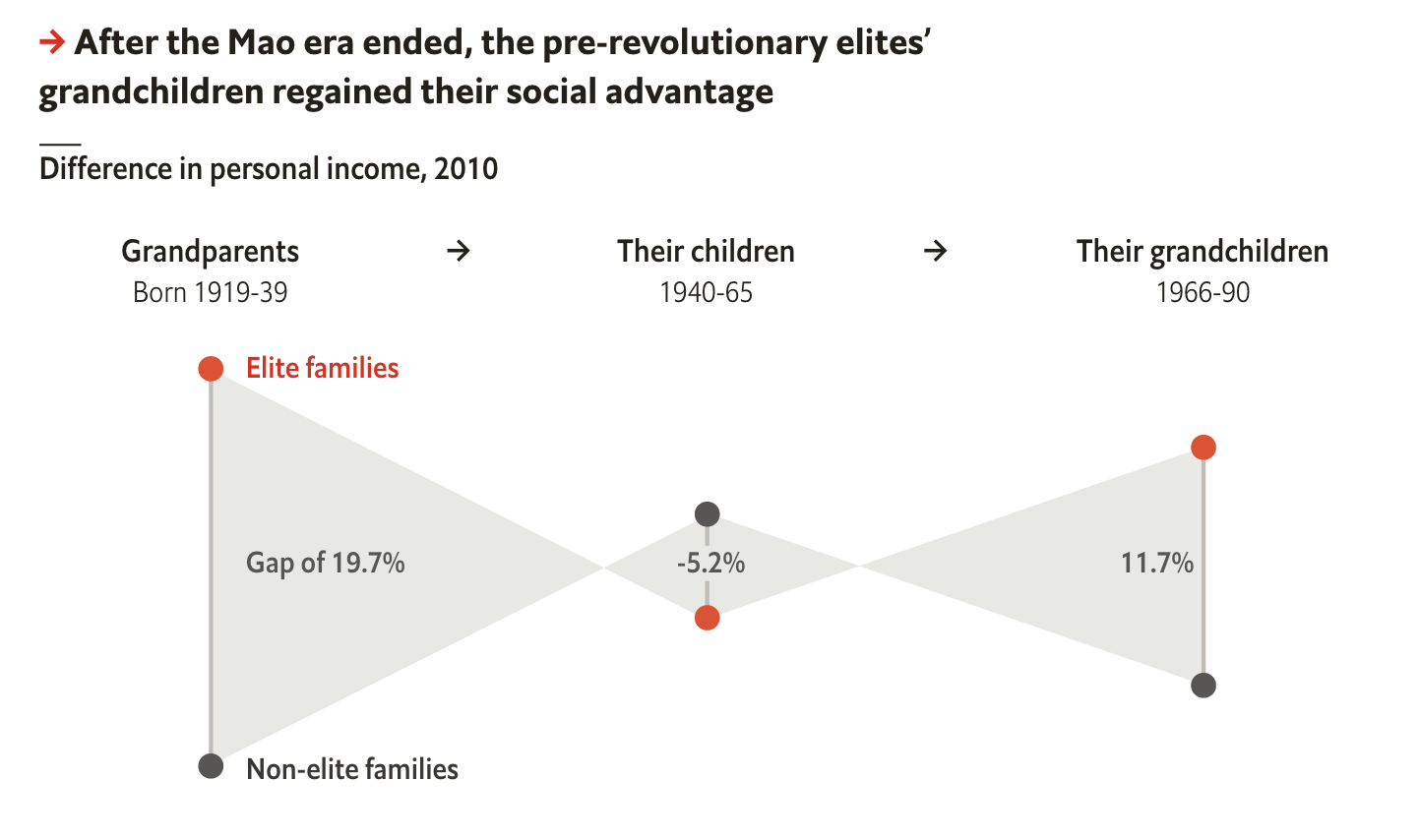

These heritability studies are difficult to design and execute in practice. How can one separate the effects of heritability and nurturing without comparing separating twins at birth and two identical twins with identical learning environments? One such alternative approach is a paper which studies the historical impact of revolutions. Particularly of note is the Chinese Communist Revolution; arguably the most levelling event in human history. The wealthy were denied education, as were the poor. The result?

Those who were wealthy prior to the revolution were poorer on average than non-elite families during the revolution — yet, one generation later, the gap was nearly as wide as it was before. Why? Clearly, this situation disproves wealth as a factor — after all, wealth was stripped entirely, and the gap flipped during the revolution. Neither is education a good explanation for the same reason. The paper lays out in verbose a few possible explanations. The first hypothesis is attitude; that the children of the formerly wealthy have more self-control and work harder as a result of family culture and nurturing. Second is the existence of “social capital” — the idea that your tribe and the resultant camaraderie leads to a better rebound from crises. On the other hand, they provide supporting data and disprove most of my uninformed guesses (decreased violence, migration away from China or areas of conflict, payments from abroad relatives, etc.) The paper concludes that efforts to eradicate inequality in wealth and education may not be sufficient to eliminate intergenerational persistence of socioeconomic status, and that policies that target human capital and social capital may be more effective in fostering mobility. I highly suggest giving the paper a read.