I.

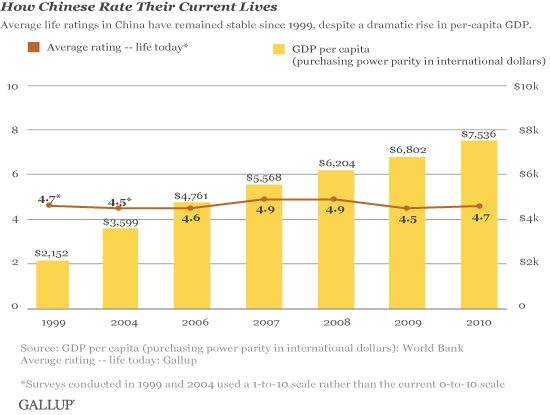

China is the greatest economic success of the late 20th and early 21st century. Globalization lifted a billion people out of poverty, fuelling China’s transition from a poor agrarian economy to a modern industrialized manufacturing powerhouse. What happened to their happiness?

This is unlikely to be measurement error, as the New York Times backs it up, going as far as to say that “Chinese people’s feelings of well-being have declined in this period of momentous improvement in their economic lives”.

This goes against just about everything I know. A prospering, wealthy middle class should be leagues happier than a poverty stricken, agricultural one. Note that this is distinctly not an argument that “money doesn’t buy happiness”, but rather using economic data as a proxy for overall prosperity. After all, back in the 1970s, China was so poor that people often suffered severe pain due to poverty (markedly poorer than India was in the 1970s.) Hunger was probably the biggest problem, but untreated medical conditions were also huge. So why hasn’t the virtual elimination of poverty itself caused the Chinese to become happier? Surely at least those who are no longer in pain are happier. If the survey results are to be believed, then any gains in happiness to some Chinese were offset by losses for other Chinese. It so follows that there is name for such a phenomenon: the Easterlin paradox. A fifty-year tug-of-war between researchers and statisticians, with the latest blow from Easterlin’s side being data from 37 countries over 30 years, including many countries that underwent spectacular growth during that time, and confirmed their original conclusion that there was no correlation.

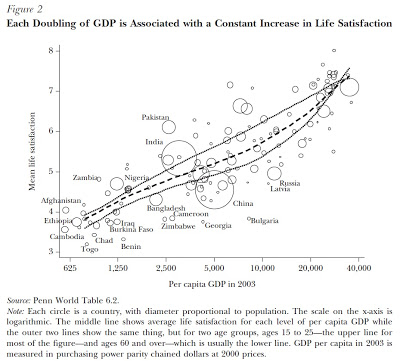

Other graphs from alternate researchers show a different truth, this one illustrating a log utility curve among entire countries

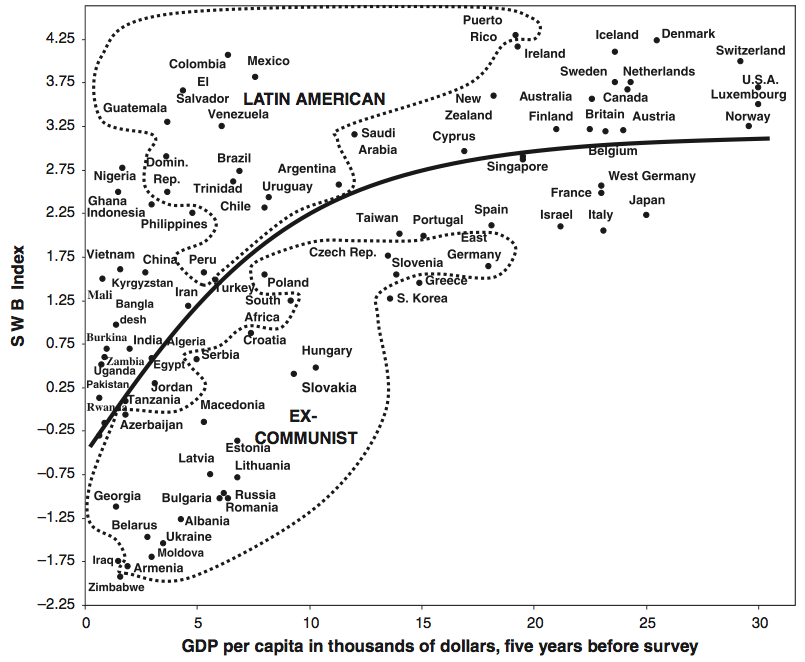

What’s perhaps more interesting is the country-by-country breakdown:

In this perceived correlation between income and happiness, there is a significant amount of cultural diversity. Even though Latin American countries aren’t wealthy, they seem to be content; Eastern European nations, while generally more affluent, appear less joyful than those in Africa, and so on. From the initial graph, one could infer that economic growth in China should result in increased happiness; yet, the other graph indicates that China’s three prosperous neighbours – Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea – all exhibit similar levels of happiness to China. Interestingly, South Korea, despite having a five-fold larger income, is not as happy as China (not to mention the highest suicide rates in the world). So, if China’s income increases fivefold, why should we expect it to resemble France or Ireland in happiness levels, rather than South Korea?

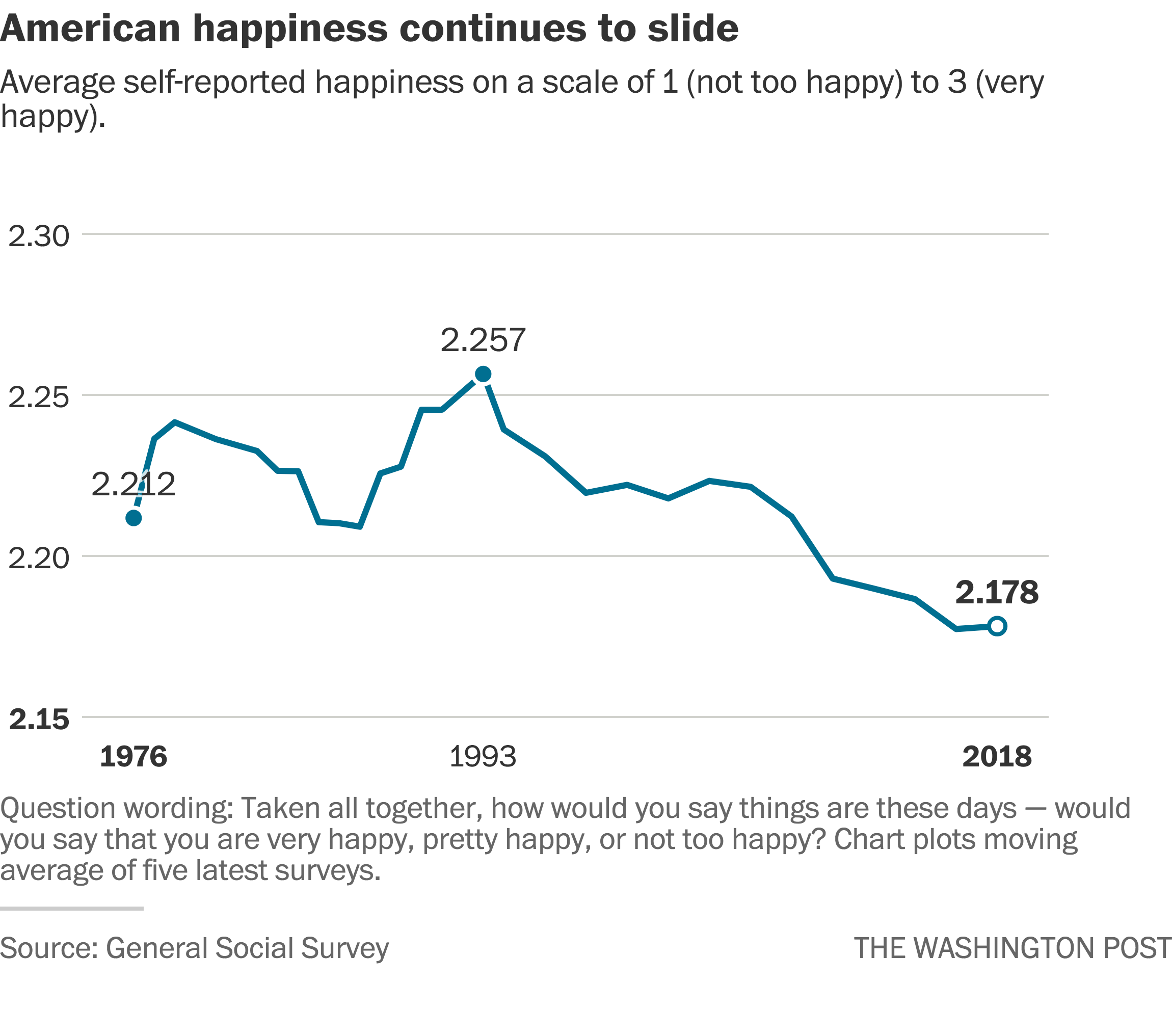

It’s easy to view this as a primarily Asian phenomena. Yet, America also shows no rise in average happiness since the 1950s, despite:

- A big rise in real wages.

- Environmental clean-up.

- Civil rights for African Americans.

- Feminism, gay rights.

- Dentists now use Novocain.

- 1000 channels in glorious widescreen HDTV.

- The… literal Internet.

I’m sure this list could be nigh-infinite. And yet…

When walking down the street, adults are no happier than the grownups when I was a child. Does this mean that all the wonderful societal improvements since the 1950s, or the 2000’s, were absolutely worthless?

The following hypothesis may seem exceptionally arbitrary, yet it aligns with how numerous individuals discuss their lives. Let’s assume happiness is typically gauged by the lifestyle people consider as “average.” As wealth grew in America post-1950, it was viewed as typical, hence there wasn’t a significant increase in happiness. The same holds true for China during its boom period. Everyone in your vicinity was also faring better, causing comparisons to neighbours. However, individuals in war-torn regions like Berlin in 1948, or currently in Aleppo, Syria, perceive their situation as abnormal, recalling peace before conflict. Hence, they report less happiness than in normal times.

There seems to be evidence suggesting that cultural attitudes towards expressing happiness vary. For instance, in Japan, openly discussing personal happiness may not be socially acceptable. At the same time, it’s plausible that Latin Americans are genuinely happier than Eastern Europeans or Asians.

Then, it’s conceivable that nothing, even eradicating widespread hunger, significantly impacts Chinese happiness levels. This might imply that the gains of one person (even if only in terms of less suffering) might correspond to the losses of another. At this juncture, those leaning politically left might raise the equality question. It’s not solely about increasing GDP, but fostering equality, as people compare their lifestyles to those of their neighbours. This argument has merit, but happiness surveys don’t entirely support it. Despite Europe being more equal, the US records higher happiness scores. Latin America, considerably less equal than East Asia, scores higher than countries like South Korea and Japan.

Assuming happiness surveys are accurate and practically nothing affects happiness barring severe war, it’s unfortunate news for all ideologues. This extends to leftists who argue that equality enhances happiness, as well as right-wingers emphasizing economic growth.

Then, perhaps this supports a theory of — and excuse my borrowing of High School physics terminology — the Law of Conservation of Happiness. Or, as it’s better known, the Hedonistic Treadmill, applied at a societal level.

II.

Picture this: on New Year’s Day, you find out you’ve won $1 billion in the lottery. It’s a well-known lottery that always pays out, no BS. They say it’ll take them a month to get the cash to you, around February 1st. Since you’re swamped all through February, you plan to start spending in March. What happens next?

Here’s what likely happens: On January 1st, when you first learn you’ve won, it’s the best day ever. February 1st, when the money lands in your bank, is cool but not as exciting. March 1st, when you begin spending, is awesome because you get to do lots of fun stuff.

Even if last year you thought your life was going to be pretty good, everything changes on January 1st when you find out you’ve won the lottery. Nothing’s actually happened yet – you don’t have the money and you’re not buying cool stuff. But your guesses about your future have soared, and that feels like happiness and excitement. Yet, on February 1st, when you’re actually $1 billion richer, it’s not a massive mood lift because you’ve been expecting it.

So what about March 1st? Let’s say you do a few specific things - you buy a fancy car, drive it around, and have dinner at the best restaurant in town. Do you enjoy these things? Almost certainly. But why? You knew all through February that you were going to buy a car and have a nice dinner today. And you knew that cool cars and nice dinners were fun; otherwise, you wouldn’t have chosen them. So why does knowing you’ll get the money mostly take away the excitement of actually getting it, but knowing you’ll get the car and dinner doesn’t ruin the enjoyment of the car and dinner?

Here’s another thought: let’s say I ate cake on my birthday every year. This is something I can predict. But I’d still expect to enjoy the cake. Why is that?

It seems like maybe there are two kinds of happiness: the kind that disappears when you know it’s coming, and the kind that doesn’t.

Happiness that’s cancelled out by predictability sounds like our old friend the hedonic treadmill: if your life gets better, that doesn’t improve your long-term happiness, because you adjust your default mental state. Something like this must be sort of true - if medieval serfs had a normal happiness level, modern middle-class people have so many advantages over them that you’d expect them to be delighted all the time, but this doesn’t seem right . On the other hand, the hedonic treadmill can’t be the whole story, or else there would be no advantage of being rich/healthy/popular to being poor/sick/shunned. But studies usually find that rich people tend to be happier than poor people.

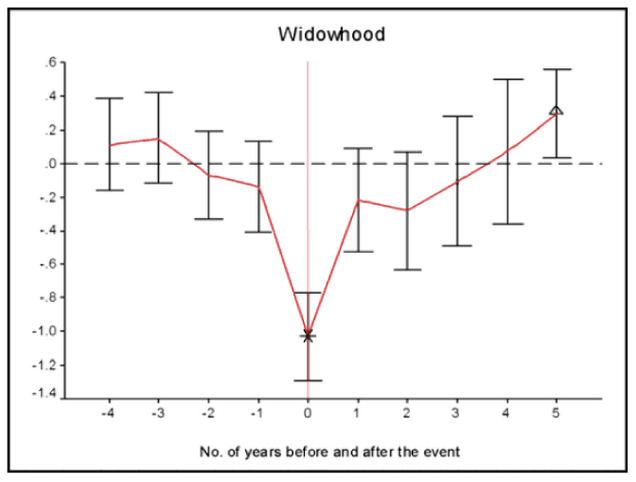

The typical example of the hedonistic treadmill is your life partner passing away, leaving you a widow. The following day, you wake up expecting them to be next to you in bed. But they aren’t. Reality is worse than you expected. Your actual emotional state is lower than what you thought it’d be, resulting in a negative effect.

Indeed, your conscious mind should be able to accept the fact that “I won’t see my partner again” the moment they pass away. This explanation implies that the subconscious mind takes longer to adjust, which seems reasonable. This isn’t to say people completely recover from the loss of a spouse (though the chart does show their life satisfaction improves).

In this situation, it seems like there’s an added layer of sadness linked to the difference between expectation and reality. It takes a few months or years to fully adjust expectations, and then you’re left with a consistent sadness. It’s the hedonistic treadmill, but heading in a negative direction instead of a positive one.

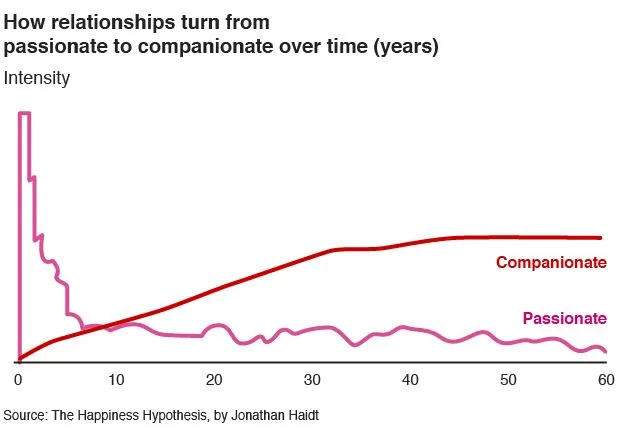

How about in the opposite direction? This (seemingly experiential, hand-drawn) graph seems to summarize it surprisingly well:

Although subjective by nature, and through my lack of trust for psychology studies, general accepted knowledge seems to confirm this. On TikTok, this is referred to as the “Honeymoon period”, a time three months to a year long where a new relationship is all-consuming, usually at the expense of all your other relationships, before settling back down again. Most advice boil downs to for God’s sake, don’t take your feelings seriously and deprioritize all your other relationships because this new one is so much better.

The honeymoon period seems like a reasonable parallel for the process of being widowed. Both last a few months to a few years. Both seem to involve updating on your life taking a surprising turn. Until you’ve fully updated, you feel unusually good/bad. After that… you return to your happiness set state.

Even Pascal and Fermat speculated on this topic with the Problem of Points

The starting insight for Pascal and Fermat was that the division should not depend so much on the history of the part of the interrupted game that actually took place, as on the possible ways the game might have continued, were it not interrupted. It is intuitively clear that a player with a 7–5 lead in a game to 10 has the same chance of eventually winning as a player with a 17–15 lead in a game to 20, and Pascal and Fermat therefore thought that interruption in either of the two situations ought to lead to the same division of the stakes. In other words, what is important is not the number of rounds each player has won yet, but the number of rounds each player still needs to win in order to achieve overall victory.

III.

I recently came across a brilliant, first-principles ML post which perhaps has parallels to human behavior.

It hypothesizes the following: reinforcement learning (RL) is a type of machine learning where an agent learns to make decisions by taking actions in an environment to maximize some notion of cumulative reward. The agent learns from trial and error, receiving rewards or penalties for actions it takes, and over time, it aims to develop a strategy, called a policy, to choose actions that maximize its rewards. There’s a common assumption floating around that RL agents are primarily “reward optimizers” - creatures that not only seek to maximize their reward but also consistently prioritize reward over task completion. But is this really the case? Or are we just projecting our human understanding of reward onto digital entities?

The article throws a wrench into this assumption. It argues that RL agents, contrary to popular belief, do not intrinsically value their reward signal. They learn to perform actions that lead to reward, sure, but this doesn’t mean they’re in it for the reward itself. They’re not sitting there, rubbing their metaphorical hands together, dreaming of the next reward. They’re just doing what they’ve learned to do.

But what about the idea that reward expresses the relative goodness of outcomes? Isn’t that what reward is all about? Reward, it argues, is more of a sculptor, chiseling away at the agent’s cognition. It’s not an optimization target, but a tool for shaping thought processes. This is easily proven by the fact that models only get “reward” during training. Then you deploy them, and they keep doing stuff, even though there is no way to get reward when inferring. It’s fair to describe this as “doing things like the things that got them reward in the past”, but not as reward-seeking.

This perspective has some pretty significant implications for AI alignment. Instead of fretting about finding “outer objectives” that are safe to maximize, we should be focusing on building good cognition within the agent. The reward isn’t the end goal; it’s the means to an end. Essentially, if a model didn’t learn to hack its reward system in training, it will not do it in deployment, even if it is “smart enough” to know that it would work.

This idea makes so much sense. I’m aware there are methods to trick my brain into feeling pleasure – primarily, using drugs. I know that if I used these methods, I’d feel a strong sense of pleasure, yet have no inherent desire to use them; in fact, quite the opposite. They would stop me from doing the activities I enjoy – in other words, the activities that have given me pleasure in the past.

What would it mean if pleasure wasn’t one’s main goal? One way to picture this is through the example of an alcoholic who can’t stop drinking, even though they don’t really enjoy it anymore. At some point in the past, drinking gave them a sense of pleasure. Now, they’ve anticipated all the pleasure away, but they continue the behaviour. If drinking ever stopped feeling rewarding (for example, if the bartender secretly swapped their regular beer with non-alcoholic beer), there would be a difference between expectation and reality, and they would eventually stop drinking. But for now, the system is stable: the alcoholic drinks, it feels just as they expected, and they keep drinking at the same rate.

My main takeaway from this article is a new commitment to see pleasure as “something that changes behaviour patterns,” instead of as a vague idea of “the goal” or “nice things that I like.” This makes the original question less hard-hitting – eating cake on my birthday might not change my behaviour, but it can still be enjoyable.

All of these examples are meant to point to a similar phenomenon: an extra kind of happiness that persists only in the context of prediction error, and eventually goes away, plus a lingering kind of happiness which can be enjoyed even after prediction error has been corrected. No classical neurotransmitter-tolerance explanation is quite satisfying logically. An alternative could be that you can’t anticipate all pleasure away – kind of like how even weeks after your partner has passed away, your brain still hasn’t fully adjusted its expectations. This would also align with a theory about desires called “active inference,” where your body creates the sensation of hunger through something like a non-changeable expectation that you’re well-fed, then allows you to feel unhappy about the gap between expectation and reality, motivating you to address it. Perhaps some lasting happiness from things like solid relationships comes from an inability to adjust the final bit of the “I’m not in a good relationship” expectation, added specifically so people in healthy relationships can still feel happy. But I don’t believe this fits with what neuroscience has shown; you can just look at the pleasure centre for simple things (like a monkey drinking juice, a common example) and find that it’s completely anticipated this pleasure (even though the monkey likely enjoys the juice just as much as we enjoy our expected rewards like fancy cars).

The fact that behaviour change is not in fact a long-term source of happiness has been a source of widespread frustration. Yet, it does make perfect sense from an evolutionary standpoint; perhaps an element of past human genetics that does not fit in the modern world. If our ancestors were permanently satisfied after a single successful hunt or forage, they might not have been motivated to repeat these life-sustaining activities. Similarly, if they were perpetually devastated by setbacks, they might have been less likely to persevere and reproduce. The hedonic treadmill could motivate continued effort and resilience. Yet, in the class-inelastic modern world, it only leads to widespread depression.