We are hardwired to be modest epistemics. Being known, seen as respected, high value, etc. is rooted and genetic in behavioural psychology of the entire animal kingdom. It’s the basis of the value of all luxury goods, social media, fashion, and the beauty industry. As if this isn’t enough, education is by definition a modest pursuit; not only does a vast majority of first world populations graduate from High School and a smaller majority from postsecondary school, but the process is one which homogenizes its participants. This effect is particularly profound among immigrant households. Grow up, do well in school, get into a decent university and study something STEM or law. Maybe business, but please, please no arts.

Only one problem: it doesn’t work.

I.

There’s not a single instance I’m aware of when parents in aggregate successfully predicted the economies of the future and prepared their children’s careers accordingly. In the 90s, everyone was having their kids learn Japanese and do outdoors leadership/executive leadership. Back then, the consensus was that you should teach your kids business instead of coding, since businesspeople would still employ the coders. Following the dotcom bubble, many believed that there would always be new computer programming languages, and therefore, one would have to work too hard just to not be obsoleted against fresh graduated. Many parents didn’t let their kids use PCs. Looking back, I was fortunate my parents were in software from the start, so we always had computers around the house. Nowadays everyone is having their kids learn Mandarin and coding; and entry-level software development jobs are nigh impossible to find (not to mention 240k+ laid off).

This anecdata is supported by a graph of historical degrees granted by subject. The four-year lag is quite amusing; the mid-2000’s peak corresponding with the height of the dotcom bubble, followed by the trough in the late 2000’s caused by the bust.

Peter Thiel put it best in 2014:

One challenge a lot of the business schools have is they end up attracting students who are very extroverted and have very low conviction, and they put them in this hot house environment for a few years — at the end of which, a large number of people go into whatever was the last trendy thing to do. They’ve done studies at Harvard Business School where they’ve found that the largest cohort always went into the wrong field. So in 1989, they all went to work for Michael Milken, a year or two before he went to jail. They were never interested in Silicon Valley except for 1999, 2000. The last decade their interest was housing and private equity.

Historically, status has always lagged behind reality by about half a generation. More recently, a headline has been making the rounds:

In 2013, 74% of Americans in this age group said college was “very important,” but by 2019, just 41% said the same thing.

In a way, the willingness to be “low status” is a predictor of future success. Folks in the status professions (banking, law, big tech) often say that they want to become an entrepreneur. But they almost never do; they attended the right school, joined the right firm, attained that corner office. At a startup, they would have to give it all up and be told by their friends and family that they’ve made a massive mistake for years, since it appears no progress is made from an external perspective.

But hey, who am I to say that I don’t seek status? After all, Zuck, Gates, and Jobs have made the whole “dropout” thing seem glamorous. I’m not even a dropout like I claim, I just never attended university. One of my favourite replies I’ve ever gotten is that “Being a dropout is only cool if you’re rich.” (h/t Calvin).

It seems fairly logical that status is an awful metric to use to optimize a career. But if not status, then what?

II.

Shortly after COVID, I began writing code for fun because I was a bored online-school student and had nothing better to do. I’ve probably done 50+ mini-projects between 2020 and when I started working full time, at which point I stopped having nothing better to do.

The outcomes of these projects was hugely skewed:

- One resulted in my first internship, doing ML back in 2021.

- Another resulted in a published paper.

- Yet another won a hackathon, earned me $20k in prize money, my first full-time job and practically invented a ~$200m industry.

- The other ~95% were completely forgettable. I couldn’t even name most of them.

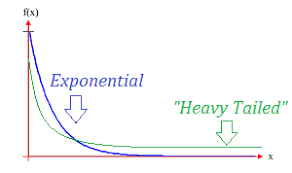

There’s a name for this distribution of results: a Heavy-tailed distribution

So-called because the “tail” of outcomes have a relatively higher chance of occurring than a given exponential relationship.

Let’s look at a few examples of this:

- Height is light-tailed. It’s a normal distribution, and the tallest people are only a few feet taller than average.

- Income is heavy-tailed; it follows a lognormal distribution where the global median is $2.5k/yr and the top 1% earn $45k/yr.

- Twitter is heavy-tailed. The median user has 1 follower, while the top 1% has over 10k.

- The cost-effectiveness of global health interventions is heavy-tailed: as measured by the Disease Control Priorities project, the most cost-effective intervention was about 3x as cost-effective as the 10th-most cost-effective, and 10x the 20th-most cost-effective.

Most people have an awful intuition of heavy-tailed distributions. My theory on why is that they don’t draw enough samples (only comparing careers with those around them, which are pre-filtered for status, etc.), and hence underestimate how good of an outcome is possible. Or, they find it hard to tell whether they’re following a strategy that will eventually work or not, so they get incredibly demoralized, and return to the default state of pursuing the path that everyone else pursues.

Being a modest epistemic works well when you have to pull a certain percentage of a population in your favour, like running for a political position and… really, not much more. On the other hand, two of life’s most crucial decisions are “one-time”: marriage and career; if you get them right, these are situations that you only need to get correct once. Hence, you don’t need to appeal modestly to the population, but rather, appeal highly to a singular archetype of individual/company. And yet, all education and parental advice centres around the idea of “keeping doors open” and being inoffensive. This is awful advice.

Taleb has a clever name for these two paradigms: Extremistan, and Mediocristan. Mediocristan are all the aspects of life that are not scalable; where no single event will significantly impact the whole. Extremistan, on the other hand, are systems in which rare events have outsized impacts. One’s life/career can of course reside in Mediocristan, but nobody actively seeks to be a massage therapist, or to be one of the 50% of marriages which end in divorce.

An important element of residing in Extremistan is the possibility for Black Swans. A massage therapist resides in Mediocristan not only because it is fairly unexceptional in income, but moreso that it has low variance. The world’s greatest massage therapist is perhaps 1-2x better than an average massage therapist, and is hard-capped by the number of clients they can see in one day (or their own physical energy). On the other hand, the greatest software developer is perhaps 100x better than the average, and it takes no additional time or energy to serve their software to billions. In Mediocristan, outliers don’t matter that much. A “2x massage therapist” can’t do much to change the world, but a “100x engineer” certainly can.

It’s a shame that heavy-tailed distributions are so unintuitive. Most important things in life are heavy-tailed:

- Jobs. Not only economically, but the countless other aspects that make a great career (a sidenote, I would highly suggest reading through 80, 000 hours).

- Scientific influence, where the top 100 most-cited papers have >10k citations while the median paper has a singular citation.

- Romantic partnerships, where half of marriages end in divorce, with second and third marriages failing at higher rates (mindblowing sidenote: this infers that the median number of “divorces per marriage” is >1?!). This in contrast with a 99th percentile relationship, presumably where a couple is extremely happy for 50+ years.

- Success of startups. In November 2021, the total value of all 3,200 Y Combinator-funded companies was $575b, and the top 5 (or top 0.2%) were worth ~65% of that (Airbnb: $100b, Stripe: $100b, Coinbase: $80b, Doordash: $50b, Instacart: $40b). The average non-top-5 company was worth ~$60m, or ~1% of a top-5, so the median was a lot less than that.

- Utility of trying new things. Most people try a lot of things in their youth, the vast majority of which are forgettable, but with any luck, a few are invaluable. For myself, I allowed a friend to convince me to go to my first hackathon which led to my love for coding. Another time, my parents enrolled me in a badminton camp at a local church, and the majority of my happiness and wellbeing in the past decade has been derived from the sport. Fiveoutofnine motivated me to try to consistently run for a few weeks, despite chronic asthma, and now a year and 2000km later, I’m fitter than I’ve ever been.

III.

I never understood the job applications process until I joined a startup and saw the other side of it. At one point, we had nine open positions receiving thousands of applications. We took none of them. In fact, the first eleven of us were all from referrals or were previous colleagues (I stopped paying attention after our twelfth hire). Why? We wanted to hire tail applicants; top 1% or top 0.1% developers. That’s hard.

Adam Smith (not the famous economist) articulates this best:

First, bad people stay on the market longer and cycle their resume around 500x more often than a great employee in the lifetime of their career.

How many times do you think the top 1% of developers send their resume to companies? Maybe 15 times during college, they get an initial job, and get to pick where they work from there out based on reputation. So maybe 30 resume-sends over their lifetime.

In a heavy-tailed context, the only way to find top 1% developers was to sort through a large amount of samples; as a startup, we simply didn’t have the time until we hired a contract recruiter a number of months later. Quite frankly, sampling from a heavy-tailed distribution can be extremely demotivating, because you do the same thing again and again, knowing it will probably fail; going on lots of dates, making hundreds of phone screens, and hearing tons of awful startup pitches. Understanding this, the recruitment process made more sense. “Data structures and algorithms interviews interviews have no real-world application,” I complained at one point. I, and the many others who share this opinion, weren’t wrong; implementing quicksort in real time on a whiteboard is not indicative of what one does as a software engineer. But that’s not what the recruitment process was optimizing for; it is intended to filter out candidates as efficiently as possible. To hire more people, a recruiter has a choice to either spend time reducing false negatives, or to simply draw another sample. Some amount of optimization is worth it, but in my experience, most people are way over-indexed on optimization and under-indexed on drawing more samples. This is especially true in recruiting. The cost of a false positive is much higher than the cost of a false negative. Firing someone is hard, but after rejecting a worthy candidate, there are hundreds more. However, finding that top 1% or top 0.1% candidate is worth all this effort since, in Extremistan, that candidate is 10x or 100x more effective than the marginal candidate.

Tech recruiting is a highly refined, rational process. It’s on you as the applicant to not be a false negative.

Other industries lean towards minimizing false positives. VC’s are often willing to invest in promising startups at absurd-seeming valuations. The logic being that if a given company is truly a winner, the most important thing was to have maximal ownership of it, regardless of valuations. In recent years, the 9-figure seed/series A round has not been uncommon. As a VC, the stupidest way you can “lose” EV is by passing on a startup, and then watch them 1000x from the sidelines. Hence, a VC’s filters would align with minimizing false positives; and as a result, VC’s invest in failed startups at a much higher rate than recruiters choose incompetent programmers. VC’s “rule in” startups, while recruiters “rule out” candidates.

It’s not quite that simple, however. One of the oddly difficult aspects of sampling heavy-tailed distributions is that one rarely starts out know just how good an outcome can get.

When I accepted my first internship, I was over the moon. I was a sixteen-year-old making the median income for my country. I had an awesome boss who was extremely formative to my worldview. I thought the founders knew their stuff, and I was getting to learn about machine learning and stat modelling on the job. I’m somewhat thankful it was forcefully ended because I had to return to high school; I would have been fairly content with it for an extended period. Yet, the very next summer, I received an offer with several multiples more compensation and was superior in every way. I don’t think it was remotely unreasonable even in retrospect to take that internship, since I did a relatively systematic search, and it was my first job so I didn’t have experience knowing what to look for. But my point is that I had no idea how much better stuff there was out there.

This is a bigger problem with one-at-a-time pursuits; such as hiring. When hiring someone, they’re filling a position; you must either fire them to try and hire someone better, or stick with them and hope they improve. Relationships are similar. Hence, one needs to know if a situation is in the 90th percentile, or the 99.9th percentile, and a wrong decision is detrimental.

On average, I expect most people would benefit from rejecting more early candidates in all situations. I recently learned of the “fussy suitor problem”. But don’t click off quite yet; I wish I had considered the problem before learning the solution. It goes something like this:

You have a single position to fill. The applicants, if all seen together, can be ranked from best to worse. You interview them in a sequential, random order, and must make an irrevocable decision to accept or reject them; logically, you can only make the decision to reject/accept an individual based on the relative ranks of the subsequent applicants. Given you would like to optimize for the highest probability of selecting the best applicant of the group, ie, the highest EV, what strategy would you employ?

The solution is…

To reject all of the first applicants, and pick the first applicant which is better than the best applicant from the first applicants, where

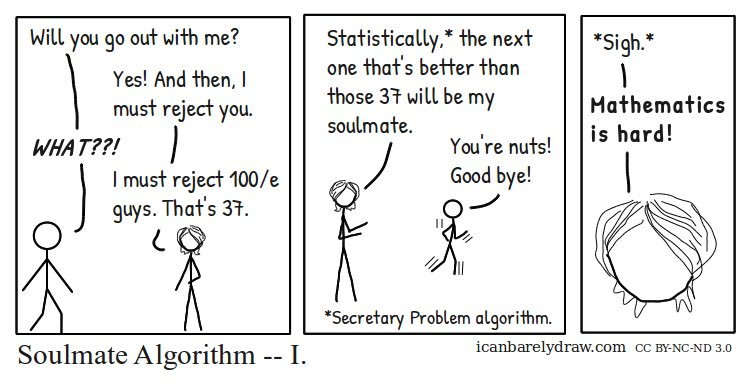

Even though it is “optimal”, the fussy suitor problem itself is more of a thought-experiment than it is applicable; one does not know for certain how many individuals one would date over a lifetime, and even if you did, living with an attitude of rejecting good things in life probably leads to extreme nihilism and insanity. A relevant webcomic:

IV.

An often-underrepresented problem in heavy-tailed distributions is the difficulty of just knowing if your process is working at all. Since the base case is failure, it’s hard to know if you’re doing anything wrong except that the counterfactual event never occurs, which happens after an inane amount of effort. As such, often the only strategy one can employ is first-principles thinking at a regular cadence.

You need to solve two problems:

- Draw samples

- Evaluate whether a given sample is an outlier

The solution to problem two was discussed in the section above. When solving problem one, it’s optimal to have a higher baseline quality. Referrals are higher signal than job applications. Friend introductions are higher signals than online dating. However, it’s also easy to over-optimize based on first-principles thinking and fall into some self-defined Goodhart’s Law.

In careers, this could be lying on your resume; you’d get a lot of phone screens and maybe even pass some technical interviews, but always get filtered out at a background check. Optimize for offers, not phone screens or technical interviews, and have some faith. In relationships, this could be manifested as catfishing. This seems to be particularly pervasive in online dating profiles; the majority of the optimization in the communities of dating app users is for the number of matches (ie, appearing likeable to the largest number of individuals), rather than compatibility (appearing maximally likeable to a minimal self-chosen group of individuals). If a recruiter optimized a listing for maximizing applicants, they would be purposefully self-sabotaging, and yet this is the societal norm in online dating. Again, the solution would be to optimize for marriages instead of an intermediary metric, and have some faith. I’m fond of the mental model of accruing fractional probabilistic “shares” of an aspiration; for example, a micromarriage is a one-in-a-million chance of a marriage (if you’re not feeling it, you could always accrue its morbid cousin, micromorts; summiting Everest is 37,932 micromorts.)

In other industries, this could look like optimizing for engagement rather than the quality of writing, with clickbait sensationalist headlines, hyperbolic, overly certain statements, or purposefully stirring controversy. Because of traps like this, if you’re working with a feedback mechanism like engagement (which is only a proxy for what you care about), it’s important to be aware of the limitations of that proxy to avoid falling victim to Goodhart’s Law. I love metrics, and know I will over-optimize whenever possible. Hence, why share my writing publicly? sidenote: as you’re reading this, i finally have adequate restraint to share my thoughts publicly, a year later.

Note that it is also possible to fall into Goodhart’s Law with problem two; it’s not an entirely unreasonable argument that the coding interview is an embodiment of this. Quantitative finance firms like Citadel and Jane Street have now turned to IQ-test-esque olympiad math and informatics competition questions (you should try them, but only if you’re cracked) to filter candidates. And indeed, many outcomes of interest have pretty good predictors; IQ correlates r=0.65 with job performance, higher than structured interviews or any other measure. At the same time, using it as a filter is partially erroneous; the very highest earners tend to be very smart, but their intelligence is not in step with their income; their cognitive ability is around +3 to +4 SD above the mean, yet their wealth is much higher than this. Surprisingly, there is a statistical explanation for this (it’s worth reading, one of my favourite blog posts). An oversimplified explanation is that IQ is arguably light-tailed since it follows a normal distribution (arguable since IQ and intelligence is not necessarily a linear mapping, but rather forcefully fit into a normal distribution by definition) while income is heavy-tailed. A subtlety here is that the traits that make a candidate a potential outlier are often very different from the traits that would make them “pretty good,” so improving your filtering process to produce more “pretty good” candidates won’t necessarily increase the rate of finding outliers, and might even decrease it. Citadel employs over 2600 quants, so this is less of a problem for them; the threshold for “pretty good” is set high enough by their brain teasers.

The optimal solutions to the two above problems are often hard, domain specific solutions. But it helps to remember that at the end of the day, heavy-tailed distributions are almost always positive sum games. An author wants to write a popular blog post just as much as a given reader wants to consume useful insights. A recruiter wants to hire a candidate to fill a position just as much as the candidate would like a job. We’re all fighting together against Moloch.

Further reading

Ordered in order of perceived usefulness

Why the tails come apart was linked in the body of the article, but is one of my favourite blogs.

I wrote an article on wealth sampling titled Status Delocalization. It explores the lognormal distribution of income and its effects.

Anu believes that to get status, you have to give up status. I found this post after writing this, but it fits the theme (also linked in body).

Jacob Falkovich writes to Kelley Bet on Everything, self explanatory.